The View from the Hill

Amidst the madness of the wettest month ever recorded on this farm, well, since 1985, these little beauties have made it their business to try to out-compete the snowdrops which are popping up everywhere. Tucked under Blackfern wood, sheltered from the east wind and sitting pretty for the afternoon sun as it climbs, by tiny increments, slightly higher in the sky every day.

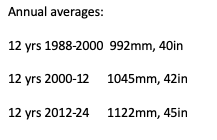

For the record, the total rainfall for January is 313mm, or 12 and a half inches in old money. The previous monthly record was 304mm in January 2014, all other months since 1985 pale into insignificance, there are 4 hovering around or slightly above 250mm, and a single one in the 280s. So we are in very unusual territory. It’s no wonder springs have broken all over the place, and many people are spending a lot of time filling sandbags, hiring pumps and nervously checking their insurance policies. The Blandford area seems to have been hit quite hard, the town centre has been closed off by flooded roads for several days, and the Stour rose to a level this week that we’ve not seen in many years.

The poor folk living in mobile homes on a council site at Thornicombe were washed out this week when a spring broke in the fields half a mile away, and began gushing forth water at an approximate rate of 700 cubic metres per hour across the fields. The soil, already at field capacity, could take no more. In spite of cover crop and stubble from the previous crop, intended to slow the water to encourage it to soak in, it simply took the route of least resistance and flowed on down to the bottom of the valley, where the main road acts as a dam, with unfortunate consequences.

Tom in Adelaide sent over this picture last week, a koala chilling in a tree in his garden, clearly unperturbed by being photographed. They are more populous than I had thought, having believed them to be a rare, precious and much revered icon of Australia, it turns out that greater Adelaide is well populated by gum trees, and hosts more koalas than the environment can really handle. They are clearly good breeders, are comfortable living in the suburbs, and this one is happy to take advantage of the water left out by thoughtful humans, being as it has been, excruciatingly hot. Up to 42 degrees recently, and this week, (hopefully) near the end of a heatwave that has lasted many days, it was 39 degrees today, when some areas further inland have reached 50 deg. Perhaps I’m happy with the rain after all.

Sheep news

Ronnie the ram was introduced to the ewes on the 6th Dec, and had covered all seven with a fetching shade of yellow within 9 days, so we look forward to a compact lambing period. The flock is smaller than for some years, due to old age taking its toll, and one ewe having lost her milk production facility during last season. We have 2 ewe lambs due to join the group next season so will have to source a new ram by then. The lamb flock was trimmed by 11 early in January – a trip to Frome market yielded good prices, unlike the grain markets, which are a pretty depressing picture. The world seems to be awash with wheat and malting barley, depressing prices back to levels we haven’t seen in a long time , whilst input prices continue to inflate, and government support dwindles to nothing, unlike the case with all our international competitors, including Wales and Scotland.

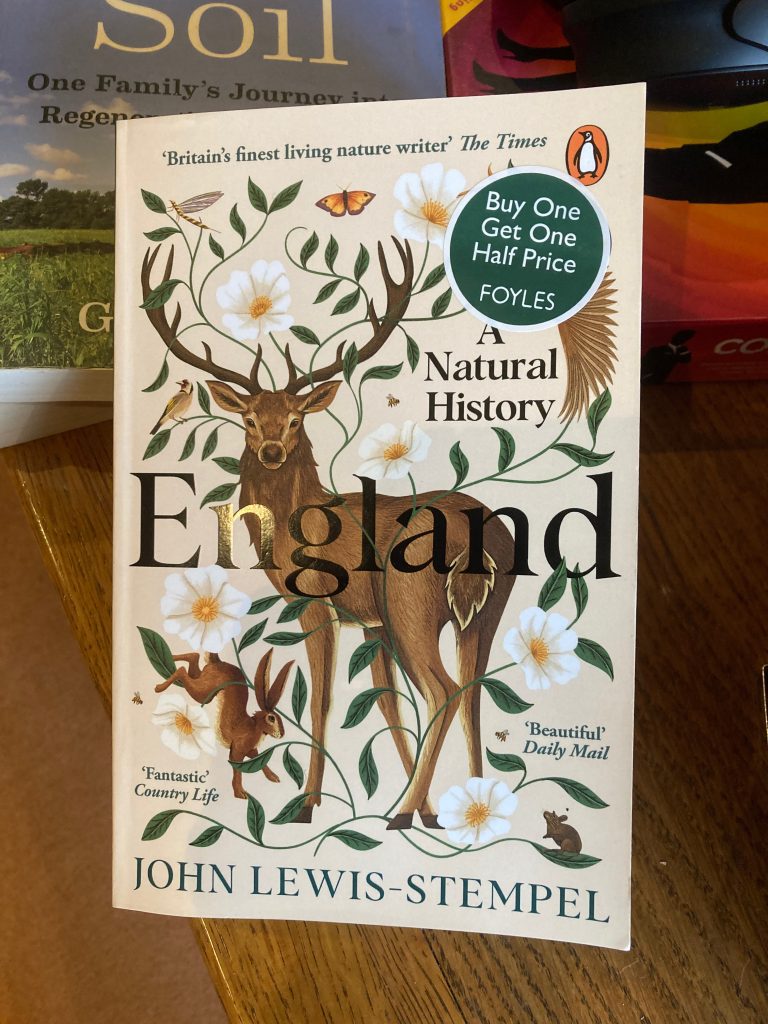

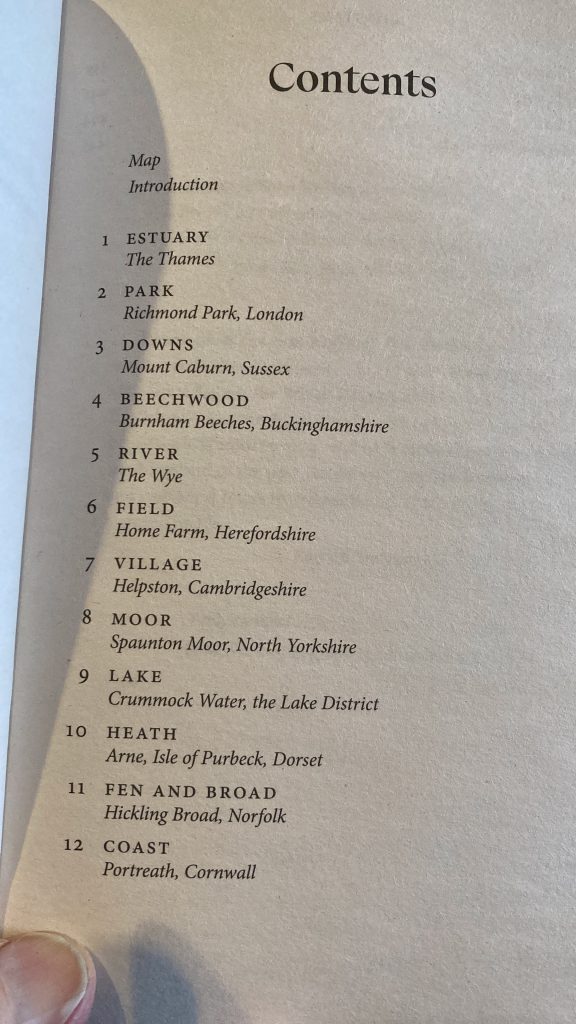

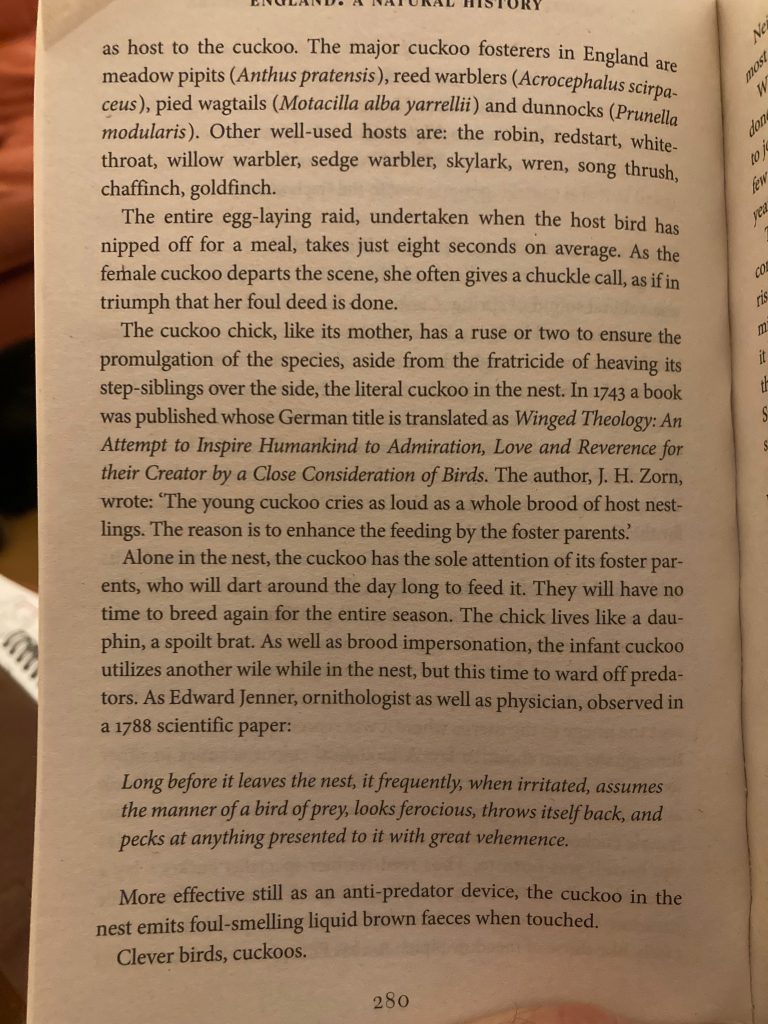

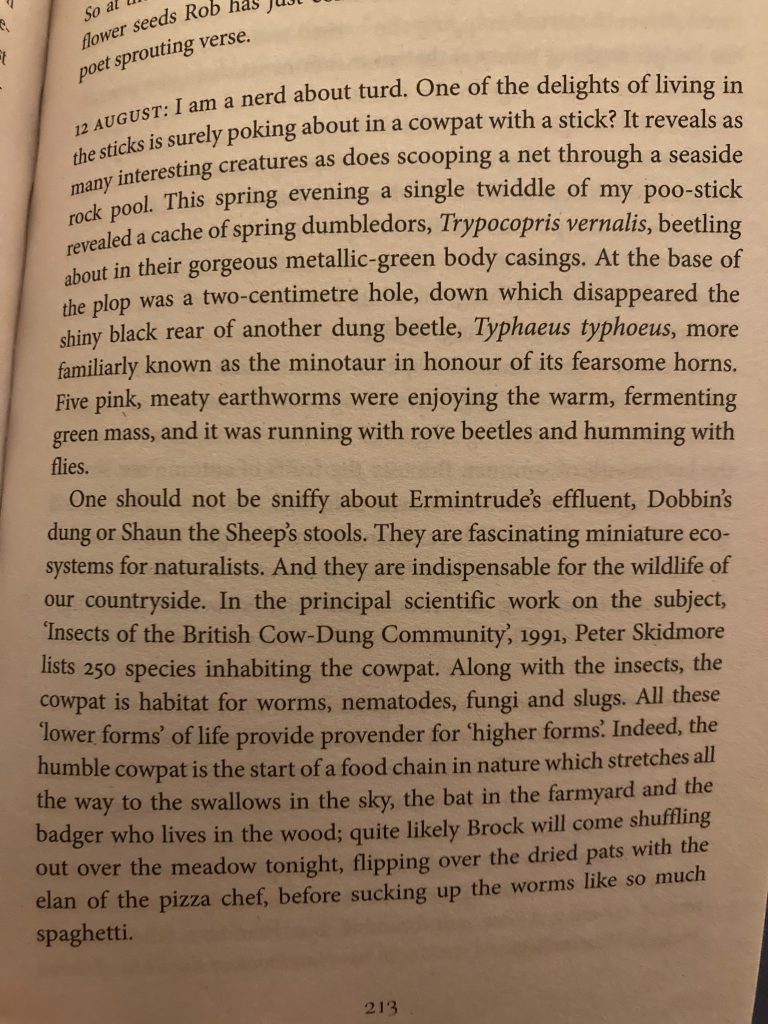

I briefly referred to this book in my last broadcast, it has captivated me for much of my casual reading time since then, and is full of nuggets I would like to share. John Lewis-Stempel is a remarkably gifted and entertaining writer who brings his extensive knowledge to the page with great skill. Each chapter is a deep dive into one of 12 distinct environments across England, with folklore, fully referenced historical perspective and personal observation woven together into a complete and wholesome piece. The first excerpt is some detail on the habits of the cuckoo, the second on the joy of dung beetles. I hope you can enlarge them sufficiently to read.

As somewhat of a contrast to Stempel’s fulsome and rounded prose, elsewhere there is a row brewing over the future of glyphosate, the very widely used weedkiller commonly known as Roundup.

There is great concern amongst many in the UK oilseed growing fraternity that the Earth is about to stop revolving.

United Oilseeds, the farmer owned co-operative that we have sold our rapeseed through for the last 40 years, reports as follows:

In November 2023, the European Commission renewed glyphosate’s approval for another ten years, until December 2033. Reviews by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) concluded there were no critical safety concerns overall.

However, the renewal came with key restrictions – most notably, a ban on its use as a pre-harvest desiccant, with countries such as Italy, banning that use in 2016.

But what works in Milan or Verona certainly doesn’t translate to Aberdeen or Perth, where crops like oilseed rape face a far shorter, cooler growing season and a much greater need for pre-harvest management.

Further to this, United Oilseeds continue:

If the UK dynamically aligns with EU plant protection product legislation again, whether through new trade agreements or alignment mechanisms, our growers could face the same restrictions without the same level of subsidy support that EU farmers receive.

Since leaving the EU, the UK has followed its own regulatory path. In 2023, the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) and Chemicals Regulation Directorate (CRD) extended the approval of glyphosate until 15 December 2026.

This period allows for an independent UK assessment of glyphosate’s safety and environmental impact, using the latest data. The possible outcomes range from:

- Full renewal (potentially up to 15 years)

- Renewal with restrictions

- Or, in the worst case, non-renewal of pre-harvest use altogether”

To this I would add, as a very very worst scenario, the complete banning of glyphosate for any agricultural use at all.

Various rape crops from recent years, largely even and weed free. Look closely at the central one however, and you can see to the left rear of the field a greener area, that did indeed ripen later than the bulk of the field. We cut the first part of the field, then left the rest to come back 10 days later. No amount of roundup sprayed legally would have evened up this field.

If we farmers insist on the need to continue using glyphosate pre-harvest I believe we can expect it to be banned for all uses pretty darn quick. Currently it is legal in the UK to apply glyphosate to most agricultural crops in a carefully stipulated period when the crop is in its ripening phase, this has been legal for very many years. The trouble is that in much of the industry, it has now become routine to treat crops in this way when farmers get impatient and think they can hasten harvest by using glyphosate on the ripening crop. However this doesn’t really work if you follow the instructions on the label correctly. The crop grains must be below 30% moisture before application, below this moisture it has been shown that no translocation of chemical can take place into the grain. The label on a can of agricultural spray is a legal document, explaining how the chemical must be used. It is a requirement in order in order to gain approval and the granting of a licence for sale and use.

There are two main reasons for use of a pre-harvest glyphosate application, firstly for the control of weeds that would make the combining process difficult or impossible, and secondly to even up a crop that is maturing unevenly, maybe due to pigeon grazing or waterlogging earlier in the season. The first is understandable, but usually indicates some kind of failure in the decision making process during the growing season. I have more of an issue with the second reason, because if you spray any part of a crop containing grains which are above 30% moisture, following the logic of the label moisture rule, there must be a likelihood that chemical could be translocated into the grain. I for one do not relish the presence of any kind of weedkiller in my cooking oil, my bread or even in my beer (made from barley), so cannot support the use of pre-harvest glyphosate, wherever it is grown. It is worth noting that many brewers and maltsters do not allow their growers to use pre-harvest glyphosate on crops destined for their maltings and breweries. The naked grain of barley differs from wheat and rapeseed, covered as they are by chaff or pods. Oats however, like barley, have no such protection, which of course is no protection at all if we believe that the chemical can be translocated into the grain anyway, should it be applied above 30% moisture, whether by accident or by design. Indeed, it also says on the label that crop destined for use as seed to grow the next season’s crop should not be treated with glyphosate pre-harvest. Does this not clearly tell us that the chemical must in some way affect the seeds?

Where glyphosate is essential, is in creating sterile seedbeds for all our crops, vital for giving them the best chance of weed free establishment, and often reducing the need to apply other much more expensive or more harmful herbicides pre or post emergence. If glyphosate is banned completely we will end up spending more on herbicides, and doing more damage to soils by the extra cultivations which will be needed for seedbed weed control.

A further note of relevance is that all ag chemicals must have a ‘harvest interval’ listed on the label, this is the latest time a product can be used on a crop before harvest, generally measured in days. It is an indication of the time needed for the chemical to be assimilated into the crop, or to have degraded sufficiently to be undetectable in the harvested grain. For oilseed rape the harvest interval for pre-harvest application of glyphosate is 14 days, and for cereal crops 7 days. It is funny how often the sun actually works faster than the glyphosate, the temptation to push on with the combine is immense once moisture is down to 14.5%, whether by chemical effect or by the sun. Many farmers now apply glyphosate to their OSR crops as a regular operation, we have proved here that it is not necessary, one just needs patience, and let the sunshine do its work..

The motivation, as so often in farming, is fear of failure, which leads to a great many applications of a multitude of agrochemicals which are not needed.

Lastly, if ‘dynamic alignment’ can manage to reverse some of the most damaging long term effects of the catastrophe that was Brexit, then bring it on. Its effect on trade in agricultural goods alone, with our biggest trading partner, vastly outweighs the cost of the loss of glyphosate pre-harvest use.

As you can see this is a complicated debate, which may have led to eyelid problems amongst some readers, but please be assured, it is a red hot issue in some quarters.

Two groups of youngstock are marching across the broad acres of cover crops in fields destined for spring cropping this year (the black dots are the cattle). They spend a day on each plot, approximately a hectare, and very happily move on every day when the fence is opened for them. The fresh grazing every day, where the animals can choose what to eat from a multi-species mixture, does them very well, they are not fed anything else such as silage, hay or straw. This approach last year led to all animals gaining weight over winter, which was not the case before we began this regime. They would then have been on a maintenance ration of hay or silage plus a thin strip of turnips every day. Not so good for the land, which would get badly poached, or for the animals, who would spent months standing in mud. There is an awful lot of electric fencing needed to graze the cattle like this, which Brendan takes on with great gusto come rain or shine, if he counted the miles perhaps there should be an award in it!

This group clearly got fed up with the miserable cold rain that set in this afternoon (Sunday 1st), they broke out through the electric fence, and were only noticed when they arrived in the yard at Shepherds Corner, clearly keen to get indoors with their mothers. Sorry chums, it’s back to the field for you. Luckily plenty of helpers were about this weekend.

On our patch of Dorset the ungrazed land on our chalk based soils drains well, even after the recent heavy rainfall periods, so moving the animals onwards daily minimises poaching. Heavy clay land farmers may weep to read this, where they have no alternative but to house their livestock over winter, and feed them with stored forage.

Theo and Mr Red, our bulls, make do with hay, some light grazing when it’s not too wet, and a pound of grass nuts every day, to keep them sweet. Which is particularly important come TB testing day, which we had to face once again a fortnight ago. The ‘Inconclusive’ animal from the 60 days ago previous test, was once again declared an IR, and so now becomes a full ‘Reactor’, which is, to be frank, a death sentence. The same was pronounced out of the blue for another animal, in a different group, who took a pretty dim view of the decision. On the day the death wagon rolled up, he couldn’t be seen for dust, well mud, and led the team on a 4½ mile steeplechase around the farm, ending up back with his peer group, he obviously knew where they were, even after 10 days of isolation with the ‘IR’ who was like a stranger to him. Cattle psychology is being studied more closely as the poor beasts have to cope with this awful disease, which the dim humans seem so utterly incapable of getting rid of. We can put men on the moon, we can ‘undress’ pictures of people on grossly unpleasant social media platforms, but when it comes to TB in cattle, we are still using a test invented in the 1890s as the first line of defence in rooting out infected animals from our herds. The SICCT skin test is very good at telling you if you have TB in your herd, but is hopeless at telling you which actual animals are infected, leaving on average 20-25% of infected animals undetected. This is the same test which is used pre-movement to tell you whether animals you plan to buy from other farms are clear of TB prior to bringing them into your own herd. What could possibly go wrong?

The NFU has helped to set up a new TB management group in Dorset, and in other counties, in the aftermath of the badger cull, to take advantage of (temporarily) lower badger numbers, and to encourage farmers to take advantage of the things that they can control, rather than agonise over the things that they can’t. On this list there are other tests that can be used, at private cost but with no government compensation for reactors not detected by government sanctioned testing. There are biosecurity measures that can be taken to prevent infection either by badgers, or by other cattle (eg neighbours’ cattle over a fence, or escapees from other farms). The careful studying of lump sizes recorded in previous TB tests, to enable a ranking of risk amongst animals, offers some hope, where farmers can manage higher risk animals in different groups, and perhaps cull them out of the herd sooner than they might otherwise have done. The size of the lump in reaction to the TB test vaccination is a reliable gauge of the animal’s reaction to the disease, the indication of prior exposure to the TB organism). Farmers can also use a service called IBTB, online, which gives access to the TB status of farms from where you may be considering buying replacements. That cow farmers do not all operate closed herds in the TB era completely stumps me, buying in cattle for your herd is like Russian roulette, you have no idea which barrel is loaded. As the vet leading last week’s meeting pointed out however, those of us who think we operate a closed herd, probably aren’t. Even if you use AI (artificial insemination not intelligence) on all of your cows, and breed all your own replacements, can you really call yourself a closed herd if you have neighbours with cows, or badgers on your farm, or even deer, which also carry TB?

Our motivation in the Dorset group is to try to ease the pain of the disease across the board, and to bring together all interested parties to try to work out a realistic way ahead, where currently we are going backwards again after the reduction in outbreaks which followed the badger cull. What the cull taught us is that reducing badger numbers can reduce the number of new TB infections, but only by around 50%, so could only ever be part of a long term strategy, but if we face facts, it is unlikely to happen again, so we have to find a different route. High on the list of asks is to get DEFRA to reassess policy, its current 25 year eradication policy is clearly a bad joke, for the reasons mentioned above. They need to constantly re-evaluate the new tests, new thinking, and the ever-changing shape of the cattle industry. Why on earth we even have a category called inconclusive reactor, let alone the options of standard and severe interpretation of lump sizes is beyond me. Severe interpretation is used in circumstances where bovine TB is strongly suspected or already confirmed in a cattle herd. If animals have reacted to the test and produced a lump they must have been exposed to the disease, therefore are an ongoing risk, to themselves and the rest of the herd. The problem is that TB is now so deeply buried in so many herds, to take out all animals that produce a lump of any size would cause mayhem, and cost a fortune. The can has been kicked down the road for decades, but if we really want to see an end to TB we need to take the disease seriously and prescribe some very painful and expensive medicine. By this I don’t mean a vaccine, the nature of the disease makes this very difficult and a long way in the future. If you then ask me why badgers are being vaccinated against TB, my answer is that it is simply a very cynical, expensive and dishonest political decision.

In case you have got this far, and still haven’t had enough, here is a flow chart used by APHA (the Animal and plant health agency) to explain the process following a TB breakdown:

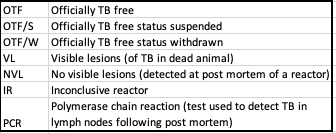

A key will help to decode the acronyms:

And in other news……

Old Harry rocks on a cold but sunny Christmas day, and across the water to the Needles on the Isle of Wight.

Essential house warming material

Swallows and Amazons on the 2nd major Stour flood of the season, shortly before Christmas

More messing about in boats, this time on the Wiltshire Avon from Bradford on Avon to Bath on a fresh and sunny Sunday in early December. Plenty of evidence of beavers, and more Kingfishers than you could shake a stick at, blue flash after blue flash, and the best sight was when one dropped like an arrow into the water, and emerged shortly after, with gleaming fish in beak. Glorious.

Next episode