View from the Hill 14th March 2020

Another day another rain gauge measurement. 7.5mm today, to add to the 50 we’ve already had in March. In the 6 months since September 1st we have measured over 1100mm, which is more than an average year’s entire rainfall. Interestingly this is so far only the 3rd wettest Sept-Mar period since our records began. The winters of 2000/01 and 2013/14 produced 1150mm in each case.

To have sown no spring crops by mid March is already cause for concern, but there are very many farmers on more difficult soils than ours who could sow no winter crops at all last autumn, who will have been hoping that we might get a fair spring sowing season, for whom it is now nothing short of a disaster. Soils high in clay content by their nature take much longer than our chalk based soils to dry out. Last night’s 7.5mm will prevent us doing any more landwork here for 2 or 3 days, but for clay soils, on top of all that has fallen recently, measure that in weeks.

In the last few days we have seen George Mogridge’s muckspreading team at work, spreading digestate and chicken manure on some of our drier fields destined for spring barley, and Gary has spent a couple of days following them, incorporating the manure into the soil. Now it has rained again we are set back further, freshly cultivated soil once re-wetted takes longer to dry out than if we hadn’t moved it at all, but how long do we have to wait without doing anything, trying to second guess when the rain will finally stop for more than 3 days at a time?

The cows have been popping out calves at a pretty steady pace over the last month. Safely indoors where they can’t poach the soil, they are munching away on good quality hay that we made last summer. That is when they can get at it. The calves have discovered it makes a very comfortable creche. This shows a disadvantage to hay feeding, they wouldn’t have done this on damp silage.

Our new ‘improved Welsh’ sheep have continued to display their talents by producing a few more early lambs, but they run off far too quickly to get any decent pictures. They continue to graze turnips, but will soon be moved onto grass so we can press on with barley sowing (weather permitting, see above).

The Durweston meadows were inundated in the middle of February, fortunately the water subsided quite quickly, even though the rain has continued, there remain a few damp patches, which attract attention from large feathered friends.

Here is the footpath from Durweston to Stourpaine near the weir at the Old Mill, wellies would definitely not be enough for a trip to the warm allure of the White Horse on that day.

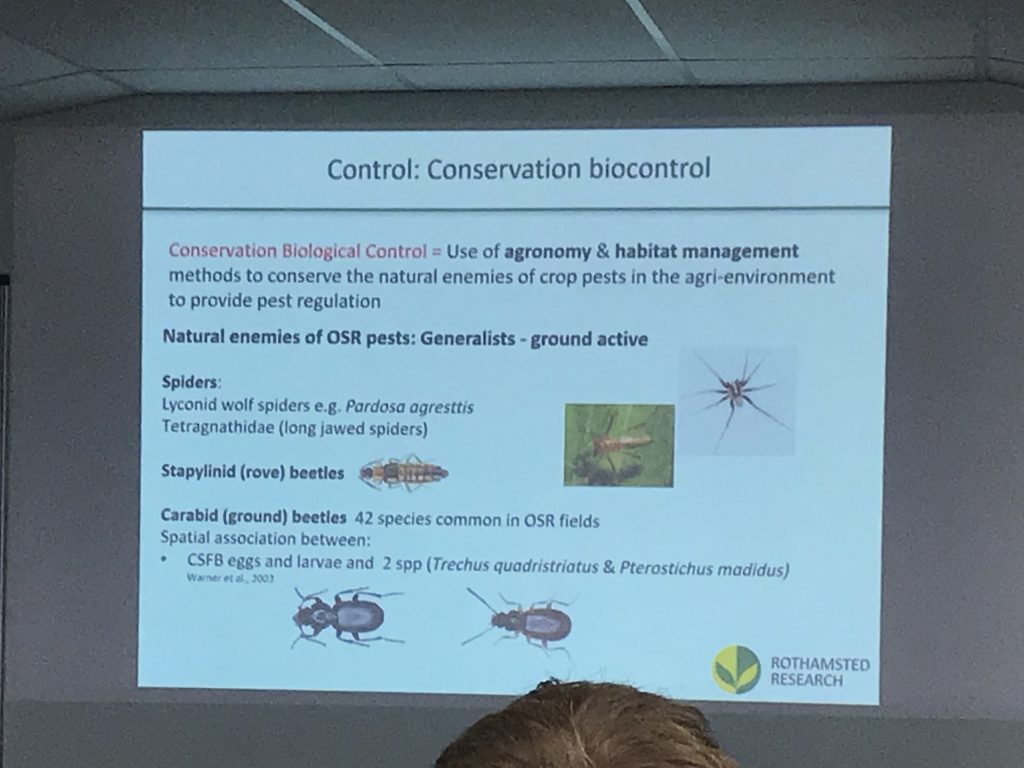

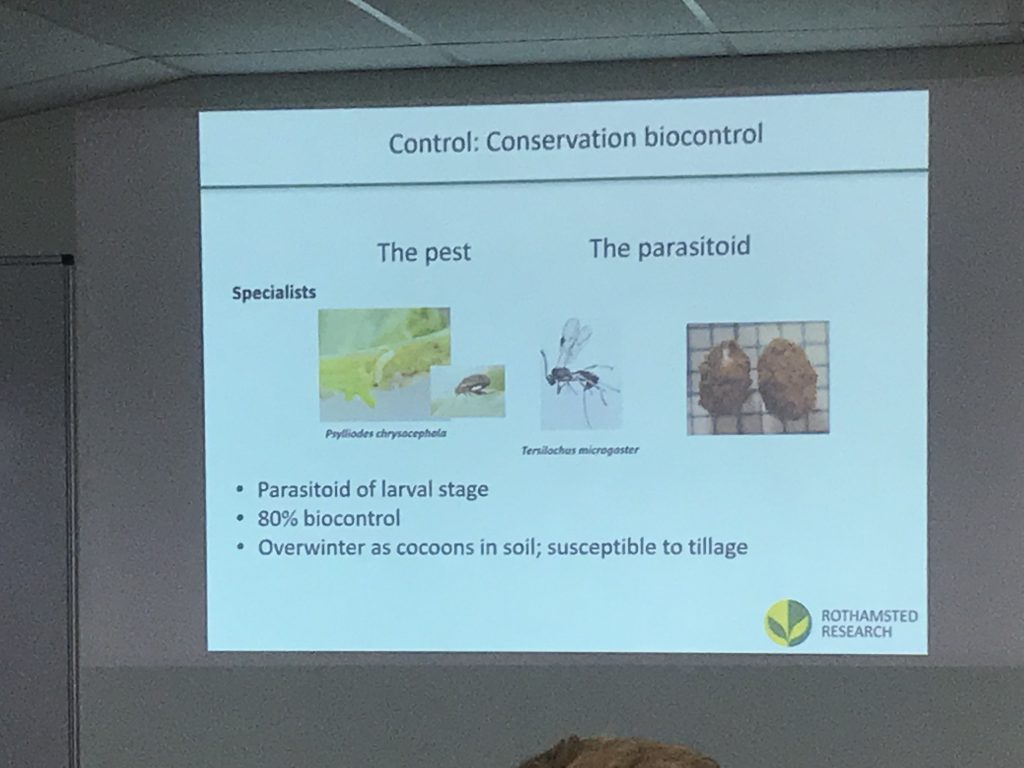

A course run in Sherborne last week by FWAG (the farming and wildlife advisory group) really lit up the debate around soils and how to improve them, and the subject of encouraging natural predator control of crop pests like the cabbage stem flea beetle, about which I have written too much these last few months. The principle of encouraging integrated pest management is not new, but is something we are re-learning rapidly as various agrichemicals are removed from the market. At times it has been too easy to reach for a can of pesticide when perhaps a longer term and more carefully thought out strategy might be better, for a host of reasons. One being that some pests (weeds, diseases or insects) are developing resistance to commonly used pesticides, so we need to think clever about how to outwit them. Not so easy if a huge cloud of millions of locusts appear over the horizon as did recently in Africa, an extreme case maybe, but that is perhaps the kind of emergency we need to save the chemicals for. The slides below illustrate some of our friends in the insect world, and we went on to discuss what we can do to encourage them. As a consequence of this meeting, we have joined the ASSIST project (Achieving Sustainable Agricultural Systems), specifically a trial to evaluate the value of establishing in-field strips of wild flowers, to provide habitat for beneficials. An early theory is that the insects will not travel much more than 50 metres into a crop in search of food, so we are going to sow strips of wild flowers in two of our largest fields, at 108 metre spacing (allowing 3x 36m sprayer widths between each for applying fertiliser and sprays, not insecticide obviously), and investigate who moves in, and long term if we see any positive effects in crops. We have to believe there’s a chance it will work, and enjoy the flowers even if it doesn’t.

Rocky helping me look for worms in the soil.

A farmer friend in Kent sent me this wet field picture, a sure sign of no spring sowing about to happen any time soon.

And another farmer friend, from East Sussex, sent me this sad picture of his wind powered water pump, which normally keeps his wetlands wetted. Not needed lately, but storm Dinnis has dealt it a bit of a blow.

When buying food, who will admit to how closely they look at the label before buying? As a UK farmer, I can be excused for doing so, I don’t want to accidentally buy some foreign grown food when it is commonly grown at home. There are plenty of other things to look at as well as where it was grown, like the ‘use by date’, the weight and the price for a start, but if you are in a supermarket, they gave up putting the price on all items years ago. Surely the most important information is what it contains and how and where it was produced ? As responsible consumers we really should care, shouldn’t we ? Not all of this information is displayed on all products, but should it be, so we can make an informed choice ? Shopping is hard work at the best of times, but every purchasing decision we make passes a message up the production line. If you buy unhealthy food produced in cruel dirty conditions on the other side of the world, using methods which are illegal here, you are sending a message to the retailer and the producer that you don’t care and that it’s fine for them to continue selling such goods in the UK. Whereas if you buy locally produced wholesome healthy food produced to high quality welfare and legal methods, you are sending a message of support to local producers and responsible retailers.

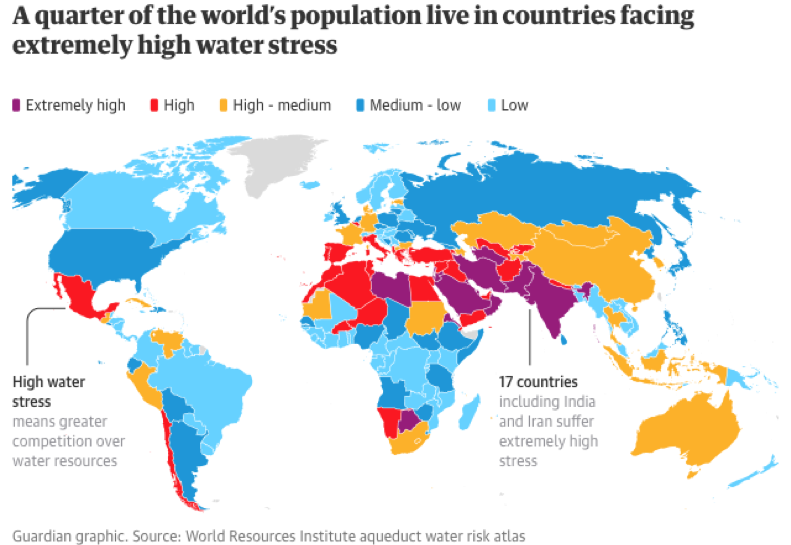

Now I am going to add another level of virtue signalling into the mix: Bear in mind that most food contains water, in fact most fruit and vegetables contain more than 90% water. Did the water in the food you just bought come from a region of the world which is under high water stress ? In the UK we are fortunate to live in a maritime climate, which means we rarely suffer from water stress. (Yes I know, the recent 6 month rainathon has caused lots of stress, but you know what I mean). So is it responsible to be importing water (in the form of food) from such countries as Morocco, South Africa, Chile, Algeria, Egypt, Spain, Italy or France, yes, even France ? The map above shows the areas of the world under highest water stress, it is quite shocking. Should we expect to eat tomatoes all year round if they come from Morocco, or lettuce, cucumbers or raspberries in every month of the year when grown in Spain, Chile or South Africa ?

Apples are a good case in point; right now, in March, you can buy UK produced apples, our local Tesco stocks them, as well as apples from France and South Africa, and I am not talking about shrivelled up Coxes here, there are lovely sweet crunchy British apples available, even though most would have been picked in September. UK growers have invested heavily in storage facilities for apples and other fruit, to extend the season of availability, so why would anyone want to buy foreign water (in the apples)?

Please could someone explain why, when Cornwall grows huge amounts of cauliflower, a winter harvested crop, grown with Cornish water, our local Tesco stocks nothing but Spanish caulis? It is a disgrace.

Before everyone jumps up and down saying that British food is sometimes more expensive than imported food, let us consider why that is. Higher food standards, such as those that apply to food grown in the UK, may cost more because we are not allowed to use cheap and environmentally damaging methods that are used elsewhere, or animal rearing methods that are cruel, or use growth promoting hormones that were banned across Europe 20 years ago. Cheaper foreign foods will almost always have a hidden cost attached, which at the moment it is still possible to ignore – the environmental cost – if you wish to.

Where does the chicken come from which is sold by the likes of KFC, or the dodgy meat on that kebab turning in the window of the local takeaway ? Restaurants, hotels and other producers of meals don’t even have to display the information you find on supermarket food, so you have little chance of knowing anything about what you are eating. But you can always ask, and even choose not to buy if no information is forthcoming. We should always read the label, and think about the consequences of our purchases.

I would add of course why is not barley flour more readily available and cheaper? It is easy to make a well risen loaf with 30% barley which of course grows well in this country thus saving the need to import hard milling wheat.

As a bonus this loaf is lower in gluten which causes many problems.

Lettuce or other salad greens could be grown in this country with protection for longer periods hopefully the ex employees from Witherspoons will continue to want to pick it. Winter squash, huge variety, not just butternut, grow well here and easy to store.

You are right there needs to be a simple planet stress labelling score 1-10 which takes into account food miles, energy input, health, co2, etc

In response to your loyal reader,my comments as follows;

In the dark ages when I was in business, Rank Hovis Southampton flour mill boasted that only UK wheats were used, They had techniques to boost the protein which obviated the need for imported high protein wheat.

Jim Atkins

Listening to a radio programme whilst the panic buying spree was at maximum, a supermarket representative said words to the effect “the UK has the most sophisticated buying system in the whole world, we can source more food at lower prices, more quickly than any other supply chain for food”

He was very proud of that, meanwhile missing out the fact that locally sourced, seasonal produce produced to much higher standards of production especially in terms of animal welfare is the most sustainable form of production in the medium and long term. Water is not the only issue albeit a very important one.

This is something that seems to have filtered through, at last, to a larger section of our population during the C19 crisis who used to think that the countryside is a sweet and lovely place where someone carving a poem into a rock on a wild hillside is the way forward because ‘they have seen it on Countryfile’ rather than the countryside being the factory floor of food production currently producing over 60% of our indigenous foodstuffs.

This figure used to be nearer 80% but successive statutory reductions in productivity – things like Set-aside and Environmental Focus Areas are reducing that capacity for food production in the UK and, under the proposed Agriculture Bill where farmers will ‘receive public money for public good’ food production is not mentioned as a public good at all.

I am not saying that the enhancing of the ecology is a bad thing, I am, like George, doing a lot more of it than I ever thought I would and it is a good and rewarding thing to be part of and to see.

The worm may have turned a bit.

Sorry about the soap box, I am a contemporary of the producer of this Blog and also a farmer over in sunny (and usually very dry) Essex with a farm shop that is currently inundated with new customers.