The View from the Hill – 14th November 2019

Rather than focus too much on the downside of the weather this month, which has been pretty universally awful for everyone, here is a picture of an attractive consequence of continuous dampness, a pretty show of tiny fungi growing in the moss at the base of a tree, with some pretty cyclamen in flower to add a bit of colour. If you screw up your eyes and ignore the flowers you could believe you were looking at parachutes floating over a thickly wooded mountainside.

In brief, the incessant rain has continued to soak the soil making it very difficult to progress with our autumn crop sowing. It is many years since we sowed wheat in November, and I only hope that it will manage to germinate as the days get shorter and colder, and that we get some kind of crop next year. Many farmers have sown very little at all this autumn, and next year’s harvest is already sure to be reduced in size.

To escape from the wet Dorset autumn, we took a trip with a group of local farmers to an equally wet Sussex to visit the Knepp Castle Estate this week. Fortunately on the day of our visit, the sun shone. The owners of this 3,500 acre estate were farming conventionally in the 1990s, but finding it very hard to make a living from dairying and cropping because the soils in that area are heavy clay, and very difficult to farm successfully. So they took the brave (some would say mad) decision to change direction radically. One might think that with that many acres it should be easy to make a profit, but if you make a loss most years because of the poor soils, then the financial problems are only multiplied by being large in size. They stopped milking and sold their cows, they stopped growing crops, and left the land to do as it pleased, and after a lot of research, they brought in animals that most closely resemble ancient species, most of which are now extinct in the UK, with the aim of letting the animals and the land find an equilibrium that would have maximum benefit for the environment, and would provide habitat for many species that have been squeezed out over recent decades by intensive farming. Their driving principle is to establish a functioning ecosystem where nature is given as much freedom as possible.

The animals they chose include Old English Longhorn cattle, and Tamworth pigs, most closely resembling wild boar, which being a dangerous animal, are not very welcome in the UK, although they are present in the Forest of Dean.

I must own up here that these lovely pictures are borrowed from the Knepp website gallery.

The estate is also home to herds of Red, Roe and Fallow deer, and Exmoor ponies. The different grazing and browsing styles of these animals is supposed to lead to mixed grazing at different heights of vegetation. One of the interesting features is finding seedling oaks growing up amongst a protective collar of thorn or bramble, which stops the animals from eating them whilst they grow to a size that will withstand some browsing when they emerge from their thorny cocoon, as shown in this picture.

The estate offers glamping and safaris, and there are a number of public footpaths running through it offering free views of the animals and the evolving landscape.

The Knepp estate is taking part in a Stork re-introduction project. 50 young storks are wing clipped, and kept in a 6 acre enclosure, shown below. After 2 or 3 years they can be considered ‘hefted’ to the area (like sheep on hill farms), and lose the desire to migrate south annually. Huge numbers of migratory storks are lost in the annual migration from Europe to Africa, either shot, or eaten by predators. The last native storks of the UK were killed by order of King Charles the second in the 17th century, who decided that they were an emblem of revolutionaries, and therefore must be done away with. The project aims to re-establish a UK based population, it is hoped that increasing areas of wild land should provide enough habitat for success.

The conversations that lead out of a visit to a large field experiment such as this are fascinating. Questions arise such as:

What is the land for?

Where should we grow our food?

How do we best balance wildlife and food production?

How do we put a value on wildlife farming?

The owner of the estate, Charlie Burrell, made no secret of the financial consequences of their decision. He assured us that in most years under the old regime, they lost money, and by the time they made their change, they were in debt to the tune of £1.2 million. 20 years ago that was a huge amount of money, even today it is very substantial. By selling all their grain, machinery, livestock and milk quota, they cleared their debts, ending up at ground zero.

Charlie explained how they then embarked on obtaining public funds to help them remove all internal fencing, and to ring-fence the estate in order to keep the animals in, this fence has to be high enough to be deer proof, 6ft. He then showed us their funding flow now, after 18 years of rewilding. To summarise, they are in a far better position now than when they were farming conventionally.

Buildings that were previously cattle sheds and grain stores now bring in substantial rents, proximity to the A24 and the densely populated south east clearly helps. Grants from government bodies for land management and conservation work make up a quarter of turnover, another quarter comes from tourism, 7% is from meat sales, leaving around 45% from property rentals.

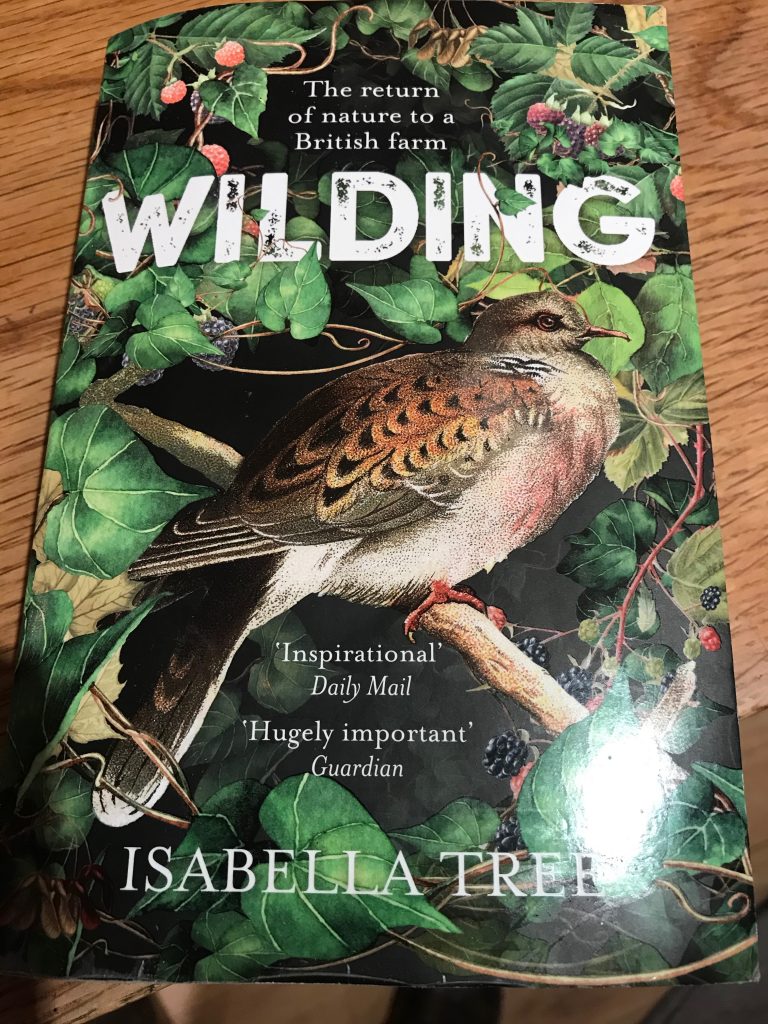

Isabella Tree, Charlie Burrell’s wife, has written a book, “Wilding”, which describes the thinking and the process of rewilding of the estate since 2000. It is a fascinating read, and explains the principle ideas behind the project. One shouldn’t expect to agree with all of it, and I certainly struggled with the chapter on ragwort, but it is thought provoking, and is certainly a very useful contribution to the ongoing debate on food and land use.

Since our visit, one or two thoughts have distilled:

A project of this nature needs a great deal of management, it is definitely not a case of shutting the gate and walking away. If you do not manage the animal numbers, you will not get the best mix of habitat for multiple species success, and would end up either with closed canopy forest if underpopulated, or treeless plain if overgrazed.

Secondly, a project of this nature is not possible without animals in the landscape, they are the tools which are used to create the right landscape for optimal multi species benefit. It becomes clear that for a healthy environment at all levels, animals are needed, and managing them correctly will produce a source of very healthy, environmentally friendly meat.

The return of the Knepp estate to some kind of non-intensive state, unblemished by artificial fertilisers and pesticides, has allowed nature to bloom, this is shown by the many surveys that are carried out, which show that many rare species have flourished, the place is alive with bird, bat, small mammal and insect life, many previously thought to be close to extinction. It shows that farmland needs careful stewardship, land which cannot produce food economically should be returned to nature. Further than that, if we accept that we will need to continue to produce food on our better land, we need to find better ways to balance food production with a healthy environment. There needs to be room for nature between the crops and animals. Is it entirely sensible to be growing grain crops to feed to animals in intensely farmed systems, when up to 90% of the grain’s energy and nutritional value can be lost when fed to animals rather than directly consumed by humans?

Simply going vegan, or turning the whole of the UK into a Knepp style wilderness is clearly not the answer. What is clear though is that it is a complicated story. More research is needed, more commitment by government and non-governmental organisations is required, to properly address finding the right balance.

I have the book and i found it fascinating, the wildlife recovery was amazing.

When you get old and don`t want the work, you should try it. More mushrooms for all !

jim

I fear it might take the general populous some to realise it can not have cheap food and a healthy environment. However if more marginal land is taken out of production ( those billion trees have to go somewhere) then hopefully prices and so a sense of food value will rise.