View from the Hill 10th January 2017

I have been taken to task after my comment previously that October is traditionally the wettest month of the year. My friend at Lazerton Farm, Stourpaine tells me that his records, which go back to 1963, clearly show December to be the wettest, a clear 10mm more than any other month of the year. Here at Travellers Rest, a mere 3 miles distant, records show October to be the wettest, closely followed by Nov and Dec, then Jan 9mm behind Oct.

The annual total to end of Dec here is 920mm, (37 ins in old money), 100mm below the long term average. December was our 3rd driest ever, at 38mm, and at the time of writing this we still have had precious little winter rain. On average, Travellers Rest receives 13% more rain than Stourpaine, although some months are the other way round.

I will stop now as I can see eyes glazing over, rainfall nerds can get in touch through the website to continue this strand.

The lovely dry cold days over the holiday period have given us a chance to carry out some scrub clearance work. Great as an antidote to too much eating and drinking. Gorse has been cut back to size where it has invaded useful pasture, and many fallen hawthorn trees and bushes have been cleared up so the animals can reach the grass underneath them. This kind of work can create a mental battleground between the tidy farmer, and the environmentalist. Half-rotted trees provide terrific habitat for insects and their predators such as woodpeckers, but where they prevent grazing, or allow the establishment of nettles, brambles and thistles, the tidy minded farmer wants to clear up a bit and make better use of the ground. As with most things in life, a balance must be found, so some trunks are left standing, and others left rotting on the ground, but much of the brush wood has been cleared and fed to a lovely bonfire.

A winter bonfire warms you in so many ways; cutting up the dead trees, dragging the pieces to the fire site, breaking up some kindling and starting the fire, throwing on the wood, fetching more, then forking up as the fire burns down. Then of course there is the physical heat to warm you to the core, the hairs which get singed when you get too close, and lastly the warm glow and profound pleasure generated from watching the dancing flames and sparks flying way up in the sky as the light fades in the evening.

Coming back next morning to fork up and see if flames can once again be coaxed out of the still glowing embers is an enjoyable challenge.

The gorse which remains is now producing a wonderful show of bright yellow flowers, a sign of the new season approaching.

Winter is a time of maintenance and repair, and over the last few weeks Gary and Brendan have been working on a stretch of new fence, where the old one’s posts had all rotted off and the wire had sunk into the grass beneath. Firstly the old fence must be removed, the tractor and loader were needed to drag the old wire out of the ground, then the vegetation was mown off before the new straining posts were knocked in. The strainers then need to be strutted, so that they will reliably hold the tension of the wire when it is attached. A rope is then laid out between the strainers to mark the straight line for the new posts, which are then knocked in, hopefully all to the same height. Annoyingly on this land, large flints lurking in the ground lend an air of unpredictability to this operation, one knock too many from the post basher can push the post crooked, or even snap it off if it confronts a large flint 12 inches below the surface.

Once the posts are all in, the wire netting can be attached to the first strainer, and unrolled along the ground. The wire comes in 100m rolls, and a second roll will be attached and unrolled from the other end. We aim to strain up 200m at a time on a good straight run. Now straining bars are attached to each end of the wire in the centre of the run, and these are then steadily drawn together with a straining winch by hand, to tighten the wire. The wires are then crimped together with soft metal crimps and heavy duty pliers.

Straining post made from old telegraph pole, with strut.

The wire, now tight, can be raised and stapled onto the posts from one end to the other. All that remains after this is to add a strand of barbed wire to the top, which discourages the cattle from rubbing and damaging the fence.

All of our lambs, or more accurately now we are into January, our hoggets, are feeding on turnips at Thornicombe, as are many of our ewes, where, for the last 3 weeks they have been entertained by a troupe of itinerant rams. Some readers will be familiar with the idea of coloured crayons being attached to the rams chests during tupping season, this is so that the farmer, or shepherd, can see which ewes have been served. After one cycle, (17 days in the ewe), the crayons will be changed for a darker colour, so that it will become clear which ewes failed to hold to the first serve. This can be seen clearly amongst the flock in the meadow of our neighbour, near the Durweston bridge traffic lights, whereas in our own sheep on the other side of the road, we do not use the crayon system, and their rumps remain white.

In the turnip field however, embarrassment abounds, as the mud on the feet of the rams betrays a certain level of activity when it attaches it self to the fleece of ewes such as the one in the picture, one of our pet ewes, hence her sheepish expression.

I hope readers will forgive me for mentioning Brexit. We can’t escape it in the media at the moment, and this state of affairs will no doubt continue for many months, if not years. Anyone who claims that it can all be sorted in a couple of brief meetings needs their head examined. British agriculture (as well as much of Britain in general) now faces the most uncertain period since I began farming, in fact since the day we joined the EEC as it was in 1973. British farmers have been somewhat shielded from the cut and thrust of world trade since then, partly on the back of the French farmers, who will spread manure in town centres, and set fire to tyres in the middle of motorways any time they feel they are not getting their own way.

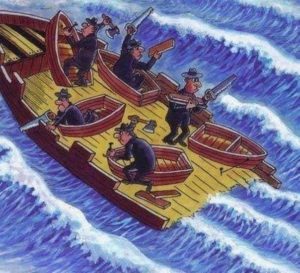

If there is no trade agreement in place for agricultural products by 2019, the date until which we are promised financial support will continue, we will face punitive tariffs before we can sell our products into the EU once we have left. Lamb for example will face a 51% tariff. Currently one third of the sheep meat produced in the UK is sold into Europe. Barley will face a similar barrier to being sold into Europe; currently we export a huge amount of barley grown in the south of England from the ports at Southampton, Poole and Portland, to brewers in Belgium France and Germany to use in their beer. Just these two commodities are essential to our own business here in Dorset. Getting the new trading arrangements right for all agricultural products post-Brexit is clearly essential to avoid the most terrifying upheaval in UK agriculture. Many view this as a great opportunity to re-map our trading relationships with the rest of the world, I can’t help but view it as the most reckless leap into the unknown.

There are many commentators who would have us believe that UK agriculture will become leaner and meaner outside the EU, that subsidies should be reduced, and farming will become more responsive to market forces. Well that last bit may be true, but we must not forget that subsidies have simply enabled us to continue producing food at less than the cost of production for very many years. Very often, the subsidy bit of our income is all that gives us a profit. Without profit we go down the tubes, and the response to market forces may be not quite what they hoped for. I have no desire to sound like a miserable old prophet of doom, however I feel strongly that some very dangerous forces have been unleashed.

We can’t expect to have our cake and eat it. Do we want access to the single market and casual labour, or not? If not, who will harvest our fruit and vegetables, milk our cows, drive our lorries, deliver our parcels, and nurse our sick and aged?

Is it too much to ask for a sensible compromise? We will get nowhere if both sides remain entrenched in their dogmatic ideology.

Look closely at a tree where it is exposed to the elements, often you will find a striking difference in the amount and variety of lichen growing on the side of the trunk facing north compared with the side facing south. Prevailing rain, wind, and sunshine favour different species.

North facing trunk of field maple tree

North facing trunk of field maple tree

Not surprised to see low rainfall records it rarely rains as much as most people think. When I used to cycle and work, people would often excuse themselves from similar exercise and non-polluting commuting by claiming they could not cycle in the rain. I would guess I actually cycled in the rain for less than ten days in the year.

What I can assure your readers is that this is not anything to do with climate change which does not exist and has just been made up by China. You only have to look at the clean air in China’s cities which the people applaud despite building a coal fired power station every day. It’s true: yes it is, yes it is, yes it is.

You are wrong about Brexit, yes you are, Brexit will make Britain great again: you should call it Great Britain. I am going to reverse the decision by Obamah to take the great out of America: from next Thursday it is going to be called Great America; yes it is, yes it is, yes it is. If you say something three times it makes it true my pastor told; yes it does, yes it does, yes it does.

Oh by the way what do you use instead of crayon raddles on your rams? I want to use the same thing. Sorry did you blink Melania? I never let my legs get that muddy.

Sounds like you are in line with your land-lord after all.