The View from the hill 7th September 2023

Frankly a harvest not worth remembering in terms of performance, though perhaps worthwhile for the things we learnt, such as how quickly the shine can be lost from a wheat variety which seemed almost too good to be true in 2022, with exemplary disease resistance, and reasonable yield, Theodore looked like a good bet for our new reduced input system. But one year is not a fair test, so a second season was essential, however resistance to brown rust fell off a cliff in 2023, resulting in fire brigade spraying to protect leaf area from being submerged under a tide of brown rust pustules. The odd thing was that where we grew it in a blend with Extase, a great variety with pretty good resistance to most wheat diseases, the brown rust developed much later in the season than when grown on its own. Yield was a big problem, grown on its own Theodore produced below 7.5t/ha, when the other varieties produced more than half a ton more, and its ‘bushel weight’, (density, in kg per hectolitre) was terrible, the lowest we have seen in any wheat for very many years. (70-71kh/hl).

We also learnt more about nitrogen rates, this was our third year of experimentation with lower rates than those we’ve applied previously. Tramline trials showed that for a difference in 40kg/ha of nitrogen, we saw yield differences of between 6% and 16%. The higher level is quite scary, but we have yet to crunch the £ numbers properly. Bearing in mind we spent a fortune on fertiliser for this harvest, bought at the peak of commodity prices a year ago, and grain prices having fallen too, the margins per ha for the lower N rates might not look as awful as the headline yields might suggest. Other farmers still using higher levels of N and sprays tell me that they have also had a poor year with wheat, characterised by poor bushel weights, always a useful pointer towards yield. It looks like 2023 has been a low yielding year for many, the very hot weather in June, followed by wet and cool and an absence of sunshine during later grainfill in July, looks to have done more damage than we had imagined. As we all too often forget, the weather always has far more effect than anything we can apply to our crops.

As soon as the fields are cleared, and the straw baled and removed, then in comes the drill, preferably preceded by a muck spreader, to sow a mixture of seeds which this year have germinated very quickly due to the intermittent rain throughout harvest. These carbon capturing cover crops serve several purposes, firstly to soak up any left over nutrient in the soil and hence reduce risk of leaching into ground water in winter, to keep active roots in the soil for as much time as possible, to give our cattle something to eat over winter, to condition the soil, and lastly to sequester carbon from the air. Using this carbon, the plants produce sugars which through the roots are exchanged for minerals and other plant nutrients in the soil, at the same time stimulating microscopic threads of fungus, essential to building soil health and resilience.

Today 7th September, we finally finished harvest, Fred managed to cut the three remaining seed plots, the phacelia, camelina and buckwheat. They all had some green material present, so we have spread them out on a concrete floor to dry them out for a few days. After cleaning these will be the seed for next year’s cover crops, along with the vetch, turnip and linseed we cut earlier in the season, and one or two purchased additions, radish and clovers. In some fields we have also added home grown peas or beans. The ones sown after barley are racing away, biomass can double in 10 days if sown in early August, but the ones sown after wheat are a bit slower. In this pic you should be able to pick out 8 species, plus 2 or 3 weeds. Pea, buckwheat, linseed, phacelia, clover, vetch, radish and camelina.

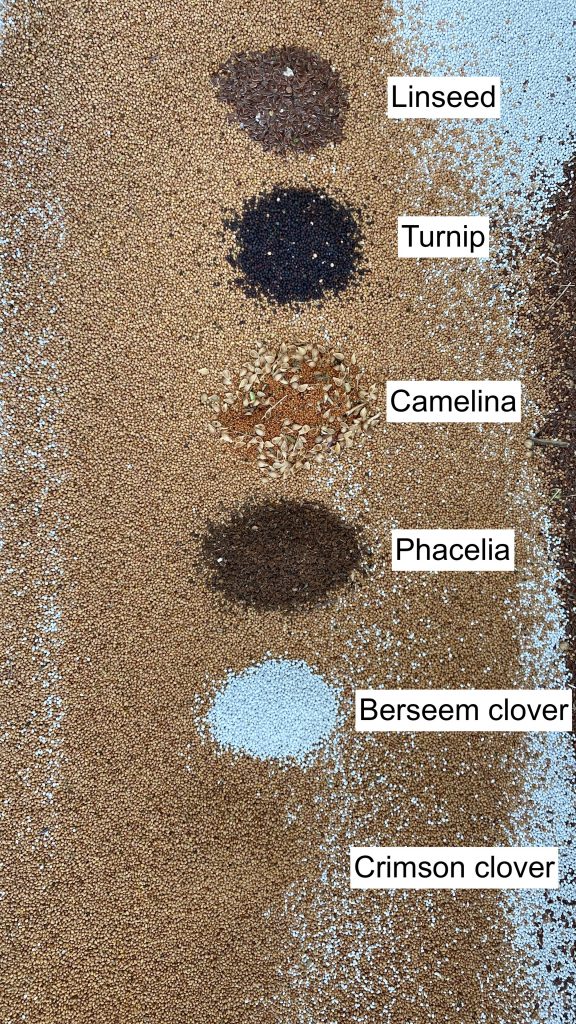

The small seeds in the mix for this year have to be blended by hand, here are examples of the seeds sitting in the bin we use for mixing. The larger seeds like vetch and peas are loaded direct into the drill hoppers, and in total we are sowing up to 10 species using all four hoppers of the drill, separately calibrated.

These seeds were used rather differently last weekend, at the county show just outside Dorchester, featuring in the craft corner of the Fabulous Food and Farming section at the show, budding young artists put them to good use making collages.

The motivation of the exhibit overall is to strengthen messages around local food and farming, and how British food is produced. All the common arable crops were demonstrated, alongside some of the processes such as pressing cooking oil from rapeseed and grinding wheat into flour and baking bread with our own baker, Paul Merry from Panary at Cann Mill. All this and more to help explain the journey to the consumer’s table. We had a life size cow (from Dike and Sons supermarket) which people could ‘milk’, a tractor quiz to test the knowledge of the machinery minded, and lots more. The show was very well attended, 60,000 visitors on both days by all accounts, the weather was very helpful, and there is loads to enjoy across the site.

Here is Fred wading through the buckwheat plot on the last day of harvest. We’d saved this up till last, as you can see there is plenty of greenery, which we thought might bung up the combine, however there was enough ripe seed to fill the tank, and once dried out this should cover our requirement for sowing next year. Buckwheat is indeterminate, which means it will keep on flowering and setting seed as long as weather conditions are right, or unless the farmer sprays it off with glyphosate. We weren’t keen on spraying it for fear of damaging germination when we eventually sow it.

A request from the sowing department a few days earlier, to go and cut the vetch because we had used up all of last year’s seed, led to an unusual sight, it is rare to see a combine discharging direct into a seed drill.

Beyond the farm gate a huge row has been caused by Michael Gove’s announcement attempting to overturn the rules requiring housebuilders to offset the potential pollution from new housing and its occupiers, by buying services from farmers to counteract such pollution. A lot of work has gone into developing schemes that will achieve this, such as those developed by the Environmental Farmers Group, a farmer-run co-operative based in Hampshire, whose business model is based around new income streams for farmers coming from private sources such as housebuilders and water companies. Gove’s announcement has blown a huge hole in this plan, and appears to have once again let developers off the hook. There can be no denying that new housing built on green field sites will bring pollution into what was previously countryside (food/wildlife/water resources). Is it unreasonable to put an obligation on the future owners of these houses to pay for the loss, and ongoing pollution that their presence will cause?

In the end, what Gove has done is to undermine a growing reservoir of goodwill that has been developing around new relationships and funding streams for farming from the private sector, in part to replace public subsidies that are right now being removed. The Basic Payment Scheme, which on many farms has for years represented the only profit achievable after production of food for less than the cost of production, this year is down to 50% of its level before Brexit, on the way to complete removal by 2027. Publicly funded schemes under the ELM banner (Environmental Land Management), specifically SFI (the Sustainable Farming Incentive) has again been delayed, we cannot yet apply, and contrary to what DEFRA have consistently said, no money will be available this year. Meanwhile they sit on the millions already saved by cutting BPS.

For a very clear explanation of what effects the announcement, should it become law, will have on environmental schemes in progress, have a listen to Farming Today from Monday 4th September, from 6 mins 20 in, where Dorset Farmer Clare explains how it would affect her business and many others: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m001q6g1

Environmentalists now fear that if the man who once promised new streams of income from the private sector whilst at the same time extolling the sunlit uplands of a glorious Brexit outcome, can perform such a shocking about-turn, are the rules surrounding BNG (biodiversity net gain) which oblige developers to provide BNG in exchange for planning permission, also vulnerable to backsliding reversal?

I particularly admire you for growing your own cover crop seed, it must save a fortune.

Harvest has generally been poor (well below average) in the East Anglian bread basket of England.

No need to despair though we can always import all the food that we haven’t managed to produce – can’t we?

Another great VFTH George. Frustrating times!

Always frustrating when government makes u turns about something that is so important and has such far reaching effects. Let’s hope that there can be another one in the right direction. This individual seems to wreck everything he touches

Congratulations on getting the harvest home and on another interesting read. With your comment “Tramline trials showed that for a difference in 40kg/ha of nitrogen, we saw yield differences of between 6% and 16%” , that’s an almost 300% variation in the difference, which begs the question “What else, besides nitrogen might explain it? So many potential variables to consider with many interlinked like plant nutrition and disease. As you say, if you could stick with 6% it might be a good call; if only it was that simple… All the best with the seed time.

Thanks George.

I always believe that livestock keep you humble, but hear your harvest story. Love the all roads to Blandford sign

Hi George.

Once again a really interesting VFTH. Carmelina – did you know there’s a long history of research into potential allelopathic effects on associated species? With flax and radish, exudates from Camelina may reduce germination or reduce P availability by inhibiting fungal/bacterial activity. There may be potential for ‘weed’ control as well as impacts on yields in species grown in mixes with Camelina. Wondered if you’d observed/suspected any such effects in the field? For accessible journal papers, just Google terms Camelina flax allelopathy.