Professor Ian Newton

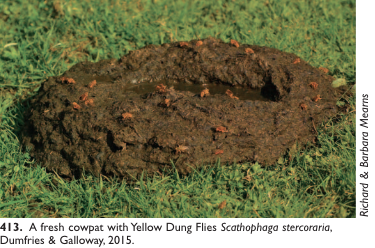

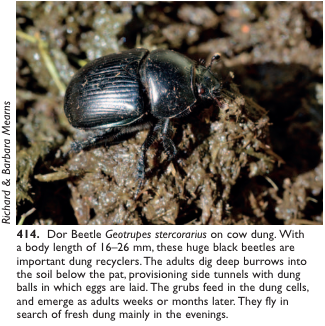

Bear with me while I explain. One of the main ecological benefits derived from domestic livestock stems from their dung which, when deposited naturally on pasture, can support huge numbers of insects. These insects in turn may serve as food for birds. My aim here is to draw attention to the importance of livestock dung in the lives of birds, and the adverse trends of recent decades which have greatly reduced its value as a source of insects. Generally speaking, large herbivores are not good at digesting their food. Typically, they extract only 10–30% of the nourishment it contains, and shunt out the rest as dung. Many small animals have evolved to take advantage of this. Worldwide, thousands of species of flies and beetles are dung specialists, and many other insects eat it along with other organic matter. Among the specialist beetles, both larvae and adults eat dung, but in many of the flies only the larvae develop on dung while the adults eat different things. Cow dung has been most studied, and each pat can feed hundreds of insects and other organisms (Lawrence 1954; Jones 2017). It is one of the wettest of types, with a moisture content of 73–89%. When it emerges, as a more or less homogeneous stream, it is fresh, fragrant and glistening, but as soon as it hits the ground it starts to dry, and a crust forms over its surface, slowing further moisture loss. Masses of flies and beetles arrive within minutes of its release, and by the second day their numbers are high, up to 200 beetles having been found in a single pat. Predatory insects arrive soon afterwards, feeding on the dung-feeders. During the first 2–3 weeks, eggs continue to hatch within the dung and insect numbers reach an overall peak, declining thereafter. By about the second week, the pat no longer attracts hordes of new visitors, but the developing larvae and maggots feed quietly within. Some adult beetles are still present, but others have moved off to new pats. By about eight weeks, the dung begins to look more fibrous. It has lost its smell and it begins to crumble, in places looking powdery, and attracting some different creatures. Gradually, mainly by the actions of dung beetles, the pat becomes buried underground, where it rots and contributes to further plant growth. Earthworms accumulate below and grass returns to the site. Standard decay times for cowpats in Britain vary from about seven to more than 20 weeks, depending mainly on ambient temperatures (Jones 2017). Different insects feed on dung at different times of year, and in addition more earthworms occur within pats in winter than in summer. In a pioneering study, Lawrence (1954) found that, on average, each cowpat produced about 1,000 developing insects. Each animal deposited 7–10 pats per day, but some were destroyed by trampling or in other ways, so he assumed six suitable pats per day. This was equivalent to 6,000 insects per day, or nearly 2.2 million insects per year (mostly flies) for each beast kept outside year-round (these estimates are not, of course, applicable to dung stored as muck-heaps or slurry). Accepting seasonal and other variations, Lawrence went on to estimate the total annual production of insect biomass from the dung of each cow or bullock kept on pasture. He concluded that ‘a cow leaves in its faeces enough food material in a year to support an insect population, mostly dipterous larvae, equal to at least one-fifth of its own weight.’ Not all insects that used the dung could be included in his calculation, so for this and other reasons, his estimate should be regarded as minimal. It also excludes worms of various kinds, which are also eaten by birds. But as a rough guide, we could say that, in five years, each cow or bullock kept outside on pasture can produce its own weight in dung insects. Many bird species in Britain exploit the insects associated with cow dung, and each pat can provide food over many weeks. Wagtails and others pick flies off the surface; Jackdaws Coloeus monedula and other corvids, Common Starlings Sturnus vulgaris, BB eye In praise of cow dung Northern Lapwings Vanellus vanellus and other waders, Black-headed Gulls Chroicocephalus ridibundus and others dig into dung pats and turn over the pieces to expose the insect larvae and beetles within. Barn Swallows Hirundo rustica and others catch the aerial insects above, as do many species of bats. Oystercatchers Haematopus ostralegus nesting on inland pastures first pick the flies and beetles off the surface of fresh pats; 10–15 days later they start to probe into the pats for beetle larvae; and after two months, when the pat has mostly rotted, they probe in the soil beneath for earthworms (Briggs 1984). During autumn and winter, the majority of cowpats present in the countryside can be pecked open by birds in search of worms and beetles. Eurasian Curlews Numenius arquata probe deeply for the larvae of Dor Beetles Geotrupes stercorarius buried beneath each pat (Potts 2012). Insects from cattle dung can be especially important to Lapwing and other wader chicks. On the Solway, such insects formed more than 80% of the diets of adult and young waders (Rankin 1979). In the Netherlands, some 21%, 30% and 49% of faecal samples from Lapwing chicks contained the remains of dung fly (Scathophaga), dung beetle Aphodius (Scarabaeidae) and soldier fly (Stratio myidae) larvae respectively (Beintema et al. 1991). The equivalent figures for Black-tailed Godwit Limosa limosa were 73%, 18% and 66%; for Ruff Calidris pugnax 33%, 29% and 46%; and for Common Redshank Tringa totanus 17%, 9% and 26%. These and other dung insects were evidently important to growing waders, and often more than one type was found in the same sample. But whereas Lapwing chicks fed on insects from within the dung, godwit chicks picked insects mainly from the surface of the pats and nearby vegetation. The other species exploited both sources more or less equally. However, there is another ‘fly’ in this story. Livestock dung deposited naturally on pasture now produces much less bird food than in the past. Not only have cattle almost disappeared from parts of the country in recent decades, but many are now kept inside buildings or yards, in winter only or year-round. In the 1950s, almost all farms in Britain kept cattle, but now the estimated figure is less than 40%. But another important development, from around 1980, was the introduction of anthelmintic drugs given to livestock to destroy gut parasites. These drugs are administered in various ways, but for weeks after dosing, they are excreted in the dung, where they last for a further several weeks, killing many of the creatures that could otherwise live in it, as well as others in the soil below, including earthworms (McCracken 1989, 1993; Madsen et al. 1990; McCracken & Foster 1994; Edwards 2004).

Dung flies and dung beetles are major casualties. The most widely used compounds for this purpose are the avermectins, particularly ‘ivermectin’ introduced in 1981. At the concentrations normally found in dung, adult beetles are seldom killed, but their egg-laying may be reduced, and larval development is slowed or prevented (Strong 1993; O’Hea et al. 2010). Fly larvae are more often killed outright, especially those of Cyclorrhapha, which is one of the most sensitive genera, showing a range of responses from death of larvae to developmental abnormalities in adults (McCracken & Foster 1993). Other British Birds 111 • November 2018 • 636 – 638 637 BB eye 413. A fresh cowpat with Yellow Dung Flies Scathophaga stercoraria, Dumfries & Galloway, 2015. Richard & Barbara Mearns chemicals are also administered to cattle to destroy other parasites. The net effects are that the numbers of insects emerging from cowpats of treated animals are much reduced compared with those from untreated ones and that, over time, dung-feeding insects have gradually declined. So much so, that a special group was recently set up to assess the current status of dung beetles and foster their conservation (the Dung Beetle UK Mapping Project, or DUMP). Little is known of the impact of this food loss on birds. However, Red-billed Choughs Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax depend heavily on dung-based invertebrates, and a halving of their numbers on Islay between 1988 and 2013 was associated with a large reduction of dung insects in the diet (MacGillivray et al. 2018). In fact, most of the bird species that feed on dung-feeding insects have declined markedly in recent decades, raising the question of how much their individual declines could also be linked with this massive reduction in food supplies provided by dung. Interestingly, organic farms now hold significantly greater numbers and variety of dung beetles than conventional farms (Hutton & Giller 2003; Geiger et al. 2010). The important message, however, is that dung insects – so important to many birds in the past – represent a sizeable component of insect loss over recent decades which has so far been largely ignored in assessments of the factors involved in farmland bird declines.

References Beintema, A. J., Thissen, J. B.,Tensen, D., & Visser, G. H. 1991. Feeding ecology of Charadriiform chicks in agricultural grassland. Ardea 79: 31–43. Briggs, K. B. 1984. The breeding ecology of coastal and inland Oystercatchers in north Lancashire. Bird Study 31: 141–147. Edwards, C. A. 2004. Earthworm Ecology. 2nd edn. CRC Press, London. Geiger, F., van der Lubbe, C. T. M., Brunsting, A. M. H., & de Snoo, G. R. 2010. Insect abundance in cow pats in different farming systems. Entomologische Berichten 70: 106–110. Hutton, S. A., & Giller, P. S. 2003. The effects of the intensification of agriculture on northern temperate dung beetle communities. J. Appl. Ecol. 40: 994–1007. Jones, R. 2017. Call of Nature: the secret life of dung. Pelagic Publishing, Exeter. Lawrence, B. R. 1954. The larval inhabitants of cowpats. J. Anim. Ecol. 23: 234–260. MacGillivray, F. S., Gilbert, G., & McKay, C. R. 2018. The diet of a declining Red-billed Chough Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax population on Islay. Bird Study doi.org/10.1080/00063657.2018.1505826 Madsen, M., et al. 1990. Treating cattle with ivermectin: effects on the fauna and decomposition of dung pats. J. Appl. Ecol. 27: 1–15. McCracken, D. I. 1989. Ivermectin in cow dung: possible adverse effects on the Chough? In: Choughs and Land-use in Europe. Proceedings of an international workshop on the conservation of the Chough Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax in the EC. The Scottish Chough Study Group. — 1993. The potential for avermectins to affect wildlife. Veterinary Parasitology 48: 273–280. — & Foster, G. N. 1993. The effect of ivermectin on the invertebrate fauna associated with cow dung. Environ. Toxicol. & Chem. 12: 73–84. — & — 1994. Invertebrates, cow-dung and the availability of potential food for the Chough (Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax L.) on pastures in Northwest Islay. Environ. Conserv. 21: 262–266. O’Hea, N. M., Kirwan, L., Giller, P. S., & Finn, J. A. 2010. Lethal and sub-lethal effects of ivermectin on north temperate dung beetles, Aphodius ater and Aphodius rufipes (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). Insect Conserv. & Diversity 3: 24–33. Potts, G. R. 2012. Partridges. Collins, London. Rankin. 1979. Breeding waders on Rockcliffe Marsh. Wader Study Group Bull. 26: 25. Strong, L. 1993. Overview: the impact of avermectins on pastureland ecology. Veterinary Parasitology 48: 3–17. Ian Newton 638 British Birds 111 • November 2018 • 636 – 638