Author Archives: The Farmer

June 2023

The View from the hill 5th July 2023

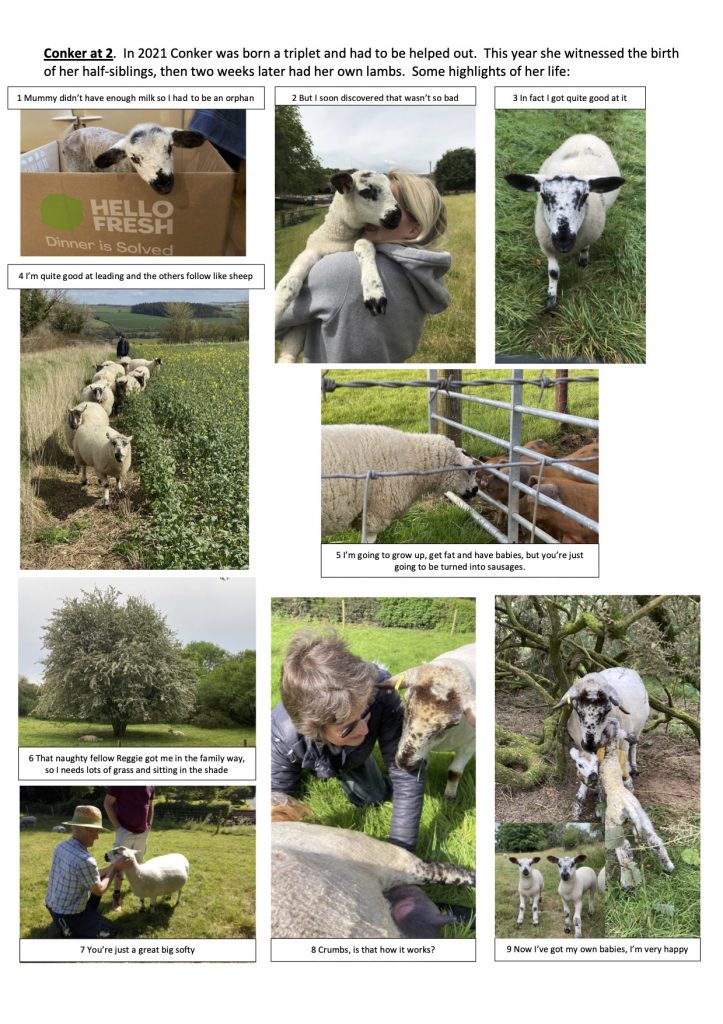

Having managed to miss an account of this year’s lambing in last month’s issue, here are a couple of pictures by way of a catch up. Reggie our young ram has done well, by ensuring that all except one of our ewes got in lamb, the one who didn’t was a bit old and nature was probably telling us she shouldn’t anyway. Our 11 ewes produced 19 lambs, which is pretty good, including one set of triplets, however true lambing percentage is worked out by number of lambs sold divided by number of ewes put to the ram. We haven’t sold any lambs yet, and we had put 13 ewes to the ram, one died and one was empty. At first glance our lambing percentage of 1.73 looks pretty good, but the true number of 1.46 is rather ordinary. How many sheep farmers accidentally forget to add back ewes lost or empty when calculating their flock performance? It’s tempting, like pub talk of yields at harvest time.

Above are Conker’s lambs, bearing no small resemblance to their mother, as you will see if you follow this link to Conker’s own page.

For those professional sheep farmers reading this rather fluffy nonsense about sheep with names, and a whole page devoted to one animal, it is worth reminding ourselves that sheep only remain on this farm for the purpose of entertainment and education. Commercial sheep farming is a mug’s game that we gave up last year after a dose of scab forced us to dip all of our sheep in a very unpleasant chemical (or rather a contractor did the dipping), which is the only reliable way to get rid of this pernicious affliction. It was the excuse needed to disperse the flock, after finding they weren’t really helping with management of oilseed rape by grazing it in the winter, neither were they encouraging wild flowers in our grass swards. The regenerative approach lends itself more to cattle grazing than sheep, cattle browse, whereas sheep nibble, right down to the ground given a chance, often preferentially eating out herbs from a mixed sward If you let them.

When dipping, you have to submerge the animal in the dip fluid completely, if not you will not kill the scab mites which live in the ears of the sheep, and control will not be complete. The rubbing, itching and wool shedding will return, and the job will have to be done again. Back in the 60’s, 70’s and early 80’s it was compulsory to dip all sheep for scab annually, and a policeman would usually attend at dipping time to ensure it was done properly. Dipping is needed for welfare reasons, the mites drive the sheep nuts when they dig in, and it is worst in cold weather. Compulsory dipping was aimed at eradicating the problem nationally. The dipping itself is of course also a welfare issue. Once the disease was nearly gone from the country, the rules were relaxed, it became no longer compulsory, but unfortunately a few pockets of scab remained, and now we are back to a situation where it is endemic. The risk of contracting it in one’s flock is huge when you buy in replacements, particularly from far off sale yards and using an agent to buy for you, as we did. Our replacement policy for many years had been to buy in retired hill ewes, usually from Wales, and expect to get another 2 or 3 crops of lambs from them. We got away with it for a long time, but got caught out in the winter of 2021. That was enough to say no more sheep, it would not have been possible for us to move to a closed flock the way we were farming the sheep then. Our tiny 11 ewe flock is scab free, and apart from the purchase of Reggie the ram last year, we will remain closed, to minimise risk of re-infection.

This is one of our wheat fields, showing the colour contrast between varieties. The smaller area of the pale one on the right, variety Champion, was the last of the seed we had sown in a different field. It’s the first year for us for Champion, it has pretty good book values for disease resistance, standing power and yield, we will see what the combine thinks in a few weeks. The darker one is Theodore, its second year for us, it had league-topping ratings for yellow and brown rust, and septoria, at the beginning of this season, however where we have been really stingey with the fungicide we have seen a brown rust explosion, which needed fire engine treatment with fungicide. Apparently we are not alone. Similarly, variety Extase, which we and every other farmer in the country is growing, has very good book values for disease, but has broken down to yellow rust in the absence of fungicide. Proper farmers will be yelling “why no fungicide?”, but having shifted our emphasis away from intensive fertiliser and chemical inputs, we are now trying to stretch the genetic ability of the best available varieties to resist disease. Having reduced fertiliser rates, which in turn reduces vulnerability to disease, a good case must be made before a fungicide is applied. Older (dirtier) varieties received a prophylactic application at T1 and T2 timings, but the supposedly cleaner ones did not, this is where we have stress tested the policy.

So having seen Theodore and Extase grown on their own with no fungicide both showing their true weaknesses, it has been fascinating to watch how a blend of the two has fared. Where the yellow rust appeared in Extase in mid May, and brown rust in Theodore a couple of weeks later, the same varieties sown in a blend have remained clean until a small amount of rust appeared on the Theodore last week, and our agronomist says it is now too late in the season to worry about treatment. The big question is what is going on? High on my list of reasons is that the plants of the same variety being separated in space by plants of the other variety means that cross infection from plant to plant is reduced. We will definitely be trying more blends next year, and trying 3 and 4 way mixes too.

We are reducing fertiliser levels as part of our desire to create healthier soils, building organic matter and biological activity in the soil improves water and nutrient holding capacity, leading to similar if not better crop performance, at lower input cost, than in quality depleted soils degraded by decades of intense cultivation and fertiliser use.

Nitrogen fertilisers and cultivations oxidise carbon and organic matter in the soil, sending carbon dioxide (CO2) and even more damaging nitrous oxide (N2O) into the atmosphere, as well as releasing water soluble nitrates downwards towards the water table. The climatic and environmental consequences are huge, and it is essential that we learn how to grow food more efficiently, without these dire consequences. Consumers can do their bit by demanding food produced by more sustainable methods, and farmers can do their bit by trying some new tricks.

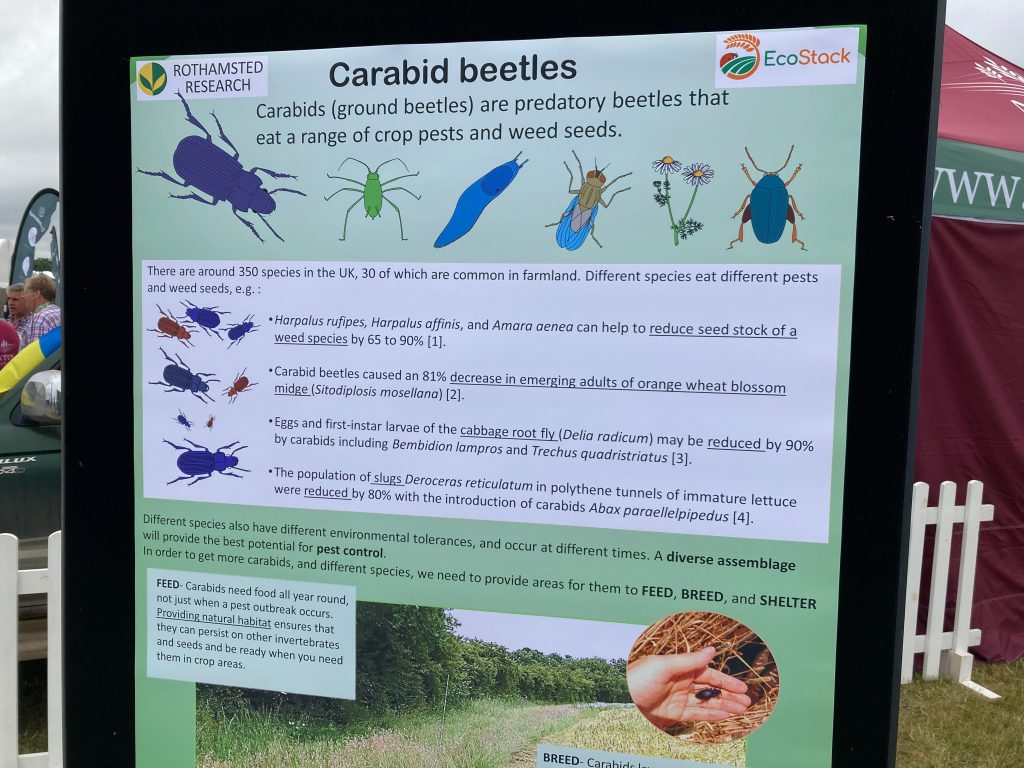

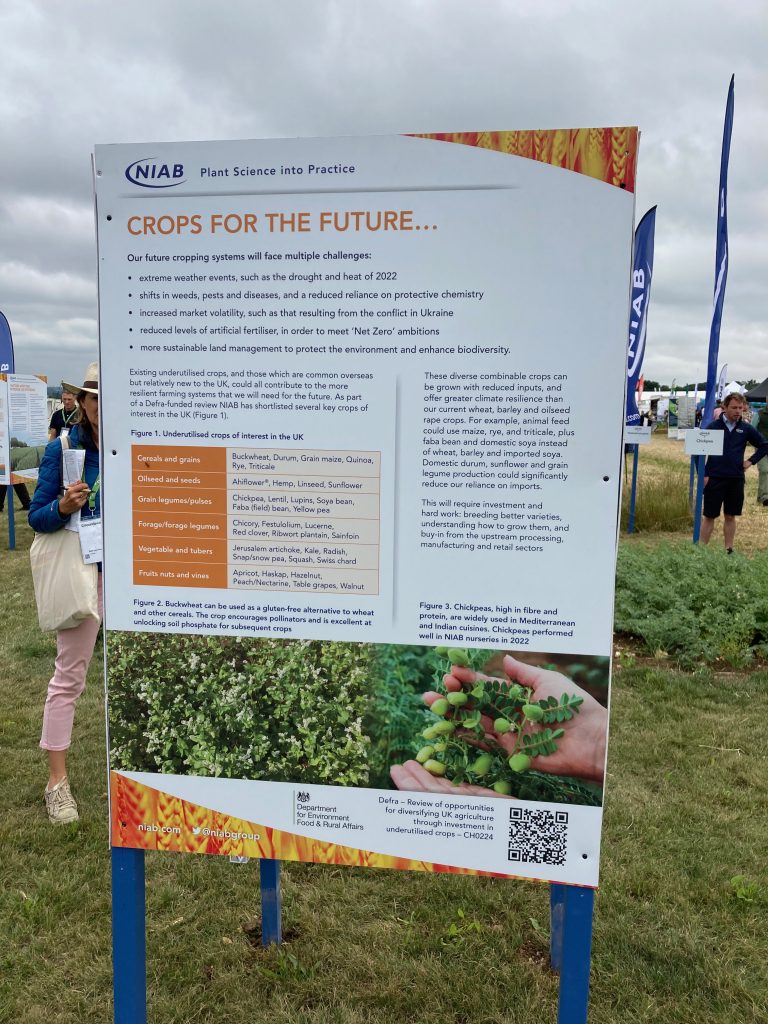

All this and much much more was on the agenda at the Groundswell Agricultural festival in Hertfordshire last week, hosted by the Cherry family on their farm near Hitchin. Groundswell steadily grows in popularity every year, and the breadth of knowledge available in talks, seminars and farmer panels, from specialists and farmers from around the world is mind boggling. Across the two days every couple of hours there would be up to 8 different sessions in 8 different tents. Somewhat frustrating, as you can only be in one place at a time, more than once there were 4 different ones I wanted to listen to. On top of this there are multiple organisations’ displays, demos and snakeoil salesmen to gaze at, admire, or avoid. There were machines on show from no-till drills to robotic weed zappers, a mobile abattoir, compost making, bat, hedgerow and moth safaris, mob grazing demos, with a smattering of music and comedy too. The hard core festival goers camp on site, some glamp, and others hotel off site, the intensity continues until late in the evening, and it is not easy to escape the feeling you must be missing something even when queuing for food or drink to keep you going. It is good fun too, to bump into friends from across the country who are also in search of a new or adjusted way forward for their farming businesses.

May 2023

The View from the hill 31st May 2023

So much has happened since I last wrote, the bluebells have been, beautiful, and gone, as have the wild garlic carpets, the rape completed its flowering, Dougal and Jules cycled from Land’s End to John O’Groats to celebrate their birthdays, and only got wet twice, the last calves were born, the bulls are now doing what bulls do, our 11 ewes started lambing on 5th May, producing 19 lambs, and today they finished (2nd June).

What a fabulous May it has been, flowers everywhere, cowslips in the fields, the May blossom (hawthorn) in the hedgerows has been amazing, often hemmed by cow parsley on the verges, followed this week by ox-eye daisies popping out in our arable flower margins. To add to the pleasure I have discovered a birdsong app: Merlin Bird ID, which is a must if you want to try learning who is singing at you every day. It is free, and remarkably effective. It records the cacophony of songs we often hear at this time of year, and disentangles them instantly listing each species as it sings, it can be played back so you can try to learn the individuals. One day last week I found a Corn Bunting and a Yellowhammer in the same place, which I would never have known otherwise.

Here is Fred raking a field of spring barley a few weeks ago, we had spread some clover seed onto the soil between the growing barley plants, then needed to incorporate it into the soil surface. Then the field was was rolled to keep the moisture in. This is experimental, and we fear it has already failed. The rake was supposed to remove some of the weeds as well, but that wasn’t terribly successful, so within a week, hoping it was before the clover germinated, we ran over the field with a weedkiller to take out the volunteer rape, cleavers and a few other things. Not much clover is apparent, do we blame the dry weather or the weedkiller ? We are trying to establish a living mulch of clover that will live in the bottom of the crop, fixing nitrogen and helping to shade out weeds, with the idea that we will sow the following crop into it and the clover continues into the next season, reducing the need for future weedkillers. The diversity of different species growing at the same time should be good for the soil, and some extra nitrogen in the system (fixed by the clover) could be useful down the road. Getting clover established in a growing crop is tricky to say the least, the weeds, stones and weather all conspire to challenge the grower.

This and many other wacky techniques were discussed at the Wildfarmed Growers day last week, at Andy Cato’s farm in Oxfordshire. Andy is a leading light with Wildfarmed, and his farm is a test bed of a good many fascinating experiments at field scale. Including co-cropping of various kinds, with inter-row mowing, hoeing and raking as weed control techniques. He was running a hoe in a field of spring wheat with spring beans while we looked on aghast, so many crop plants were being pulled up, as well as the weeds, eventually Andy called off the machine, a steerage hoe with cameras to ensure the hoe tines run between the rows, not in them. There is great scope for this kind of technology, as accuracy and reliability improve, but right now I can’t completely silence a voice in the back of my head which says surely one little dose of weedkiller would be a lot easier, and certainly less of a challenge to any ground nesting birds or more likely their nests, in the field at the time of hoeing or raking?

We were also given a bread making demonstration by Richard Snapes of the Snapery Bakery in London, he started by showing us how to create a simple starter. A sourdough starter is a stable mixture of beneficial bacteria and wild yeast that’s maintained with regular refreshments and is used to leaven and flavour dough. It takes the place of the regular yeast that is used in most bread making. The yeast for the sourdough starter is derived from wild yeast spores floating around in the air at the time, which enter the mixture and begin the fermentation. Richard then moved on through the stages of creating loaves, using doughs and finally loaves at different stages that he had prepared earlier. Sourdough bread takes longer to prepare than the Chorleywood process used in most modern mass production bread making. With a longer fermentation, the bacteria in the starter break down much of the gluten in the dough, which can result in a bread more easily digestible, and be more suitable for people with gluten intolerance. We ourselves have recently purchased a small stone grinding mill, and are looking forward to baking with some of our own Wildfarmed wheat flour after harvest.

This talk of bread brings me to the price of food. There has been much talk recently of food price inflation, and even of some mechanism to persuade UK retailers to impose a cap on the price of certain staple foods. I wonder how that would work? The main reason that there are shortages of eggs and other food products in some supermarkets today is because many of those supermarkets are incredibly resistant to raising returns to primary producers such as farmers and horticultural growers, for fear of losing their competitive edge with their fellow retailers. Farmers’ reaction to this when faced with huge costs (energy in particular) and poor prices for their output, is simply to not restock their chicken houses in the case of eggs, or plant up their glass houses in the case of salad veg. Farmers receive only a tiny proportion of the value of the raw materials they produce as it is, so they are not well placed to suffer price reductions. Processors and retailers need to be called out to explain their margins and profit levels. Some kind of mechanism for fairness and honesty in the food chain is required.

UK food is the 3rd cheapest in the world after the US and Singapore, and the proportion of the average income spent on food is between just 10 and 12%, whereas it was very much higher in the past. The Food Security summit held at No 10 a couple of weeks ago nibbled around the edges of the problem, but didn’t come up with much of substance. We will still face uncertainty whilst rampant profiteering is allowed to continue, at the expense of the environment, the producer and in defiance of common sense.

April 2023

The View from the hill 30th April 2023

Suddenly spring is here, though not exactly convincingly. While we’ve been spending too much time indoors because it has still been cold and wet through much of April, everything outside has been getting on with it in spite of the weather. Many farmers have been complaining that the grass isn’t growing fast enough for them to be able to let their animals out of their winter quarters, and others say the ground has been too wet and bovine feet will turn everything to mud in a flash, but there is no denying that things are indeed growing, like this lovely patch of wild garlic and bluebells together next to the river Stour just upstream of Durweston. We are just about at peak spring flowers now, and it is essential to get out and enjoy them. Bluebells are always a joy to brighten a dull day or mood, and an unbroken carpet of garlic, as there is in one or two local woods, is like a fresh fall of snow, though considerably smellier, which one barely dares spoil with a footprint.

Here are some cowslips that just get better and better every year, on a 10 acre field which we reverted to downland under stewardship, in 2010, using seed harvested from the flowery steep banks nearby, the flowers have improved as the fertility has depleted, meaning the grass gets less competitive allowing the flowers to proliferate. There are many species here, including a few orchids, and if we manage the livestock grazing correctly, allowing the flowers to set seed and spread each year, their coverage improves.

The earlier calving cows, and their calves, which were born from the beginning of February onwards, have been out of doors for a few weeks on drier fields, the calves are growing really well, and the cows are slowly filling out after their winter hay diet of the last 5 months. We just need for them to shed the remnants of their scruffy winter coats, and start to shine, then they will look a whole lot better.

This year’s 6 new heifer entrants to the herd were introduced to Mr Red last week, but they didn’t seem to know quite what to do with him. He will be with them for the next 3 weeks, then he will be let loose with a larger group of the older cows for around 9 weeks. Theo the (red) Hereford will take care of the other group. The purchase of these two new bulls last year, both red in colour, has proven to be a great success, we now have a lovely crop of multi coloured calves, with more variation from Theo than from Mr Red, (Angus) who carries the recessive red characteristic. Readers who were paying attention last month, and who have at least a rudimentary understanding of genetics, will recall that although red in colour, he is an Aberdeen Angus, where the most common, and dominant, gene carries black colouring. Most of the cows and heifers that Mr Red served last year are at least ¾ black Angus, so many of his calves have come out black. However of note are the twins belonging to Ginge, our one red heifer from last year, which are a gorgeous red. Pictured here at Websley when they were smaller.

One fine day 2 weeks ago, we made the tricky decision to get on and shear our tiny sheep flock. We found a very good shearer, Mike, locally, who came along to shear our pregnant ewes with care and precision, very few were nicked in the process, and all looked very smart after their trim. There were a few cold nights following, so they were allowed to sleep in a barn overnight, we didn’t want anyone going into premature labour from environmental shock. We are now waiting patiently for the arrival of some lambs, hopefully starting around May 5th. At shearing time we convinced ourselves that they are all pregnant, which is a significant improvement on last year. The ewes are now back in the paddock nearer home where it is easy to keep an eye on them.

There is little doubt in my mind that when a ewe looks like this, there is a good chance she is carrying at least one lamb.

Whilst on livestock, it wouldn’t be right to omit mention of this year’s trio of piglets, who arrived around 3 weeks ago. Greedy as always, the weather has made it very easy for them to turn their paddock into a ploughed mess far quicker than their predecessors of the last 3 years, when we had very dry spring weather and the soil was far less pliable.

They come from a farm near Milton Abbas, where Maureen Case runs a small pedigree herd of Oxford Sandy and Black pigs, with 7 sows and 2 boars. These three gilts came from the same litter, they were 9 weeks old when we picked them up.Here is another (younger) litter, of 11, it turns out that there is always a runt of the litter, the big ones bag the more milky teats at Mum’s front end, and the smaller ones have to make do with the smaller yield of the rearmost teats. The big piglets get bigger and stronger, not for a moment concerned with the welfare of their smaller siblings. Watching ours when we feed them, one is reminded why they are called pigs, ear biting and barging is commonplace in order to secure the largest portion of the ration. One of ours was clearly a front end guzzler, she is bigger than the other two and doesn’t hold back.

The Blackthorn winter has certainly lived up to its name this year, much of April has been cold, and the Blackthorn has flowered vigorously for a long time, hopefully that will mean plenty of sloes for next autumn. Blackthorn is an important host of the Brown Hairstreak butterfly, which lays its eggs on young blackthorn twigs, the caterpillars hatch and remain on the blackthorn for much of the year, before eventually emerging as a handsome butterfly with a dark upper wing surface, and a contrasting orange underside. Over-zealous hedge trimming can eradicate populations alarmingly easily, but once we have learnt this kind of fact, farmers are usually keen to help, and soon grasp the importance of every other year trimming, or longer term hedge management incorporating coppicing or laying, often supported by environmental schemes, which pay farmers to adopt beneficial practices.

As the blackthorn flowers fade, we find the hawthorn is in bud and will very soon deal us another beautiful snowy blanket along many of our hedges and bushes.

I got very excited a couple of months ago when I discovered that a farmer friend I knew from the Tisbury area was as a sideline importing and propagating Dutch elm disease-resistant Elm Trees. Ancient maps of the Durweston area show trees in clumps in several of our fields, which I feel sure would have been elms. Back in the 80s I remember digging out the remains of huge tree stumps from our meadows near the old Durweston mill. At the time we believed these to be Elms, the last of the great many that used to populate the countryside before Dutch Elm disease laid waste to them. The disease is caused by the fungus Ophiostoma novo-ulmi which is spread by elm bark beetles. It got its name from the team of Dutch pathologists who carried out research on the diseases in the 1920s. Ash dieback disease now threatens another mainstay tree of the English landscape, the sight of hundreds and thousands of ash trees succumbing to the disease is enough to reduce one to tears of sadness and frustration. Anyway, in an attempt to remain positive, this story is about the efforts of a small number of dedicated plantsmen to try to resuscitate the English Elm. There has been work in universities across the world to develop resistant elms and these hybrids are subjected to inoculum trials to assess their resistance to Dutch elm disease.

While these resistant strains look similar to English varieties of elm, they are described as exotic species. They might not perform exactly the same ecosystem function so replacing elms with them is not necessarily a complete solution. My farmer friend had a small stock of a cloned variety called Lutece available, which has become the most widely planted of the modern hybrids in Britain, through the efforts of Butterfly Conservation and the Island 2000 Trust on the Isle of Wight. Sadly its extended dormancy in spring may prevent it from becoming the resource for the White-Letter Hairstreak butterfly that it was once hoped to be. In our case, the 9 specimen trees that Peter supplied are all budding up nicely, and I am hoping to obtain more next winter so as to be able to complete a line of them along the road between Durweston and Bryanston. For further information please have a look here https://resistantelms.co.uk/elms/ulmus-lutece/, or here https://www.woodlandtrust.org.uk/trees-woods-and-wildlife/tree-pests-and-diseases/key-tree-pests-and-diseases/dutch-elm-disease/

There is a lot of debate surrounding the original appearance of the Elm in Britain, and its subsequent development, generally it is not a strong breeder, and very often spreads by suckers rather than seed, perhaps this made it more vulnerable to disease? Further interesting debate here https://www.wildlifebcn.org/sites/default/files/2021-07/Complete%20key%20to%20native%20and%20naturalised%20elms.pdf

Some dissected wheat plants from last week, showing development stages, this helps us to decide when is the best time to deploy fungicides or other products to help the plants fend off disease. The first key timing is when final leaf 3 is fully emerged, this leaf makes a small but significant contribution to final yield, and by keeping it clean, we can help slow the spread of disease to the uppermost leaves, especially the flag leaf, which can contribute as much as 50% of crop yield. You may be able to see from the picture that the variety on the left, Palladium, is some way behind the Extase on the right. Extase is an early developer, and therefore a good indicator as to the likely growth stage of all the wheat in a given season. The flag leaf, once fully emerged, is therefore the most important target for expensive inputs. This year we are trying out products to boost the plants own defences against disease, as well as carefully deployed fungicides, which have become eye-wateringly expensive. Our policy of choosing varieties with the best resistance ratings against disease, combined with a reduction in rates of fertiliser, should reduce disease pressure, and the application of silicon and salicylic acid are aimed at boosting plant defences, rather than simply attacking the fungal crop diseases with fungicides, which could be counter productive when we are also trying to encourage fungal growth in the soil. Mycorrhyzal fungi in the soil are intimately incorporated with plant roots, and are essential for conveying sugars (carbon) from plant photosynthesis, into the soil, as well as for sourcing minerals from the soil to feed into the plants, too much fungicide can impede these processes.

In a further attempt to reduce our reliance on fertiliser and chems, we are trying out bi-cropping, in this case, growing spring wheat and beans together, reducing the risk of disease for both crops, and contributing diversity to the soil and environment. Once harvested we will attempt to separate the wheat and beans with our ancient cleaner. They are being grown on contract with a company called Wildfarmed who encourage growers to try more environmentally friendly farming methods by finding premium markets for the produce. https://wildfarmed.co.uk

March 2023

The View from the hill 29th March 2023

This year’s calving has romped on at a great pace. The 21 heifers all finished several weeks ago, and most are in the yards at Websley with their calves. The main herd started at the beginning of March and over the following 3 weeks popped them out at a good rate, we are down to less than 10 now, the busiest day saw 8 born, and yes it was a Saturday, during the 6 Nations rugby tournament. Doug and Brendan had to sort and tag 10 calves on the one day, before they get muddled and we lose sight of who belonged to which cow. This little fellow demonstrates clearly why we decided to bring in a Hereford bull, Theo, as a change from 100% (black) Angus, irresistible with the white face, red body and fluttery eyelashes, we didn’t really need to write the bull’s name on her tag, but it has become a habit, so that we avoid embarrassing partnerships 2 years down the line, when we bring new heifers into the herd. Our other bull, Mr Red, a recessive red Angus, has produced some lovely coloured calves too, like the twins I mentioned last month, bringing even more visual variety into the herd. It will take a cleverer person than I though, to properly explain the genetics of the recessive red Angus, suffice to say he will throw calves of different colours depending on the colour genes carried by the mother.

One day last week we had to turf out one penful of cows into a nearby paddock so we could use their pen for sorting out the youngstock, who have been outdoors all winter, but have run out of grub. They have worked their way across all the cover crop fields, munching off the mixed species covers at approx 1.2 hectares per day, this at least means that we can in theory get on and sow the barley that will follow, except that the unusually wet March we are experiencing has prevented any tractor action in the fields for the last 3 weeks. 140mm so far, the average for March being 74mm. The younger ones were heading one way, to a field where we can feed them silage, and the older ones were heading across the farm towards the river meadows, where there is some grass. While the cows were outside, enjoying a thin bite of grass on a brisk day, two of them decided to calve, just in the two hours they were outside.

The cows get mucked out a couple of times during the winter, so that they don’t end up jumping over the gates or banging their heads on the roof of their shed. The muck gets hauled out to the fields where it will be composted with woodchip, anaerobic digestate, and maybe some green trimmings, before spreading in the autumn. It can be tricky juggling the handler if we have muck to move, and grain lorries to load, you can’t just drive it from the cow shed, covered in muck, to the grain store, it takes at least half an hour to wash it thoroughly, and then the tyres if still wet, will stick to grain, carry it outside and spread it all over the yard. We always try to avoid mucking out when lorries are due, but some of the grain merchants can be a bit ‘short notice’ with their collections, or perhaps it is the haulier, one can never be quite certain. One unfortunate driver had to wait rather too long the other day after a misunderstanding with his boss. We had cows temporarily outside, making a field muddy, and the clock ticking for getting the mucking out finished before dark, new straw bedding needed to be spread before the handler could be released, for washing then loading, with wet tyres anyway.

The spring barley is making an appearance this week, having been sown in the first few days of March the cold and wet has not encouraged it to emerge in a hurry. What it would like more than anything now is some warm sunshine and drier days so it can get on and grow away, and keep ahead of weeds and disease.

The 22/23 winter hedge planting campaign has at last drawn to a close, our target was 1,700 metres of new hedge, plus a quantity of gapping up where we’ve coppiced off some old and gappy hedge under our Stewardship scheme. With the aid of a team of very keen helpers from Durweston, and others from Bristol, we’ve managed to plant around 12,000 plants when the weather has allowed, over the last three months. Most of it now needs fencing in to keep cattle and marauding deer out, and this will keep Gary and Brendan busy in every spare moment when crops and cattle allow, for several weeks. It is great to see that some of the earlier planted whips are already leafing up or even flowering, the ‘pussy willow’ catkins of the Goat Willow have looked good but are already past their best now, as the leaves appear. The cat paw like catkins indicate a male plant, and it is to be hoped that we also planted some female ones, so that fertilisation and fruiting may occur. The female flowers are less showy, but offer plenty of nectar to attracts insects like bumblebees, with luck bearing pollen on their bodies, in order to successfully pollinate.

Other early flowering species which are already providing plenty of pollen and nectar for the season’s early emerging insect population include Gorse and Dandelion, which provide food for a longer season than most other flowering plants. We’ve also got Lesser Celandine just showing its face, in a beautiful clump around a tree in the paddock across the road. This photo is from last year, on 26th March. We are going to be several days later this year.

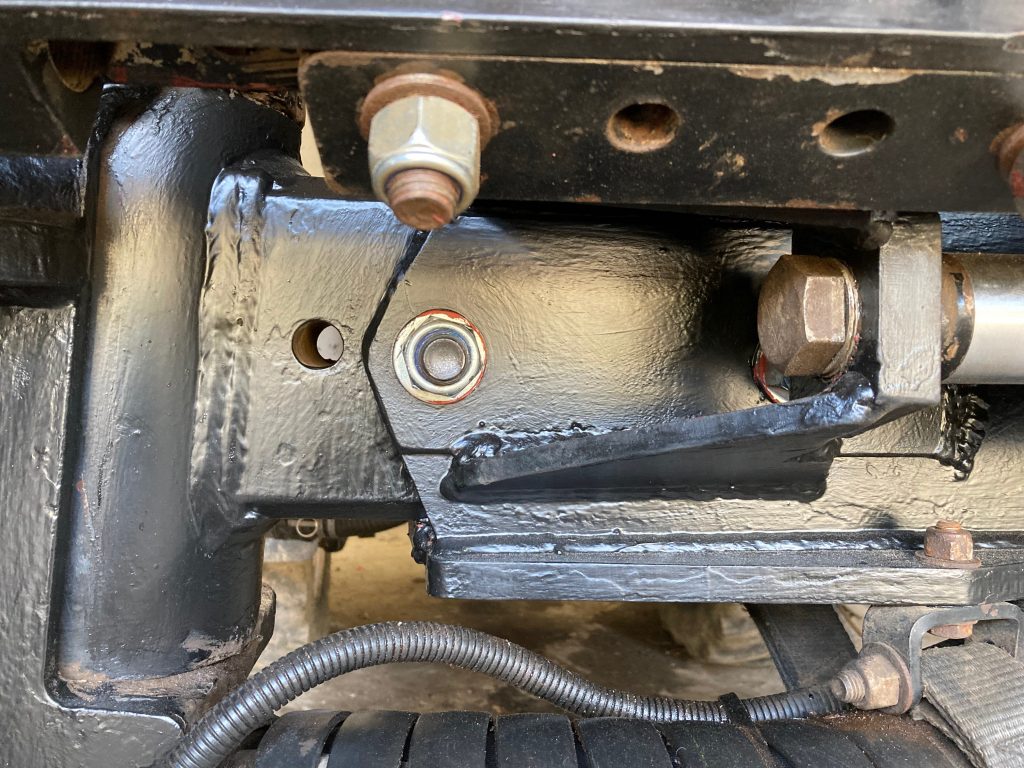

A bit of skilled engineering was called for last week, so a call went out to Drew, who kindly came along to help, as always endlessly resourceful and steady of hand. The problem was the rear axle of our Knight self-propelled sprayer. For several years it has been intermittently breaking the bolts that hold the sliding sections of the adjustable axle together. All the weight of the machine seemed to be riding on 4 bolts, as the machine aged (it is now 10 years old), what was once a snug fit had stretched and worn, so the bolts took all the strain. A short term bodge had involved inserting some shims between the inner and outer axle sections, which prolonged the life of the bolts, except the one which had rusted itself in solid. The effect of the shims though had been to open a crack in a weld on the outer section, so the bullet had to be bitten. Apologies for a bit of in-depth engineering talk, there could be at least one reader who will be paying attention in Essex.

A fantastic new tool which Drew brought along, that we hadn’t seen here before was an annular holecutter that will fit into an ordinary drill chuck on a portable drill. We are familiar with broach bits as used in a Mag drill, but had not seen them in a form that can be used in a portable. As engineering minded folks will know, anything larger than 12mm conventional twist bit in a portable drill is a pretty unwieldy thing, and it is very easy to blunt the outside edges, the area that does the most important cutting when drilling a hole. Whereas the multipoint cutter remains sharp for ages, and can be safely used up to 25mm or beyond if used carefully, which of course is where Drew comes in. At £40 a pop, these bits must be handled with respect.

The problem we had was the rusted-in bolt, 12.9 hardness and 20mm diameter, it was in an awkward position behind a bracket that the steering ram fixes to, which gave no straight aim for a hit to bash it out, or to drill out in one go. Until we removed the first 10mm of the bolt we could not remove the inner axle to then drill out the rest. Steady-hand Drew managed to cut the bolt head off at an angle to allow him to then drill out the first 10mm, freeing the axle to be pulled out. Then the rest of the bolt could be drilled out, a good eye and a steady hand being required again to drill the bolt itself and not the surrounding casting.

Once this was done, some cleaning up, fabrication of strengthening plates and welding them into place could proceed. Repeated on both sides, back and front, this repair has hopefully ensured safe and reliable service for a good while. Brendan gave the whole area a thorough wire-brushing, red oxide primer and top coat finished the job.

And Finally…….

February 2023

The View from the hill

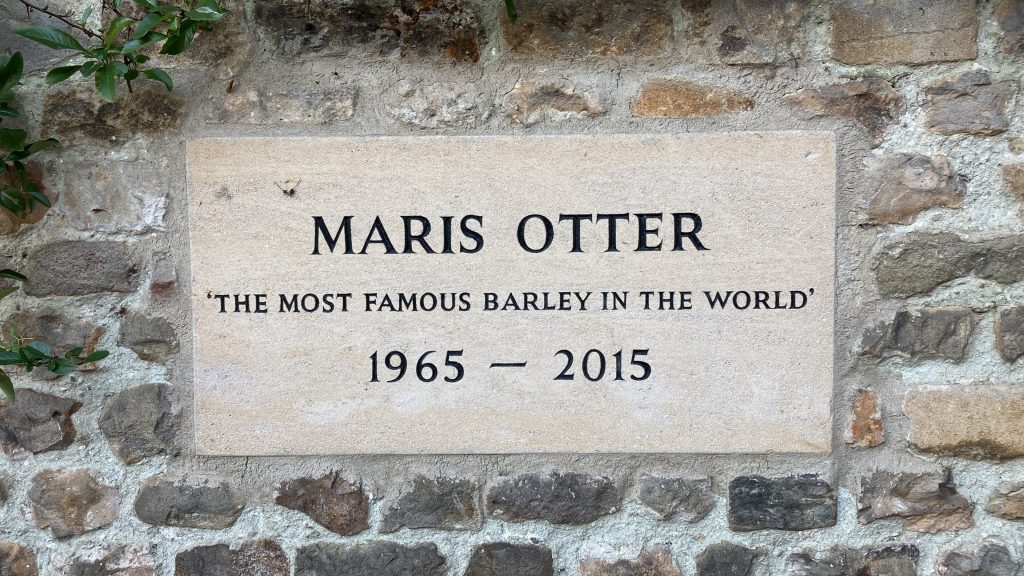

For the last few weeks we have been loading two lorries of barley per week for Warminster maltings. We are still growing Maris Otter barley, now 58 years since it was bred at the Plant Breeding Institute (PBI) in Cambridge. There are also a couple of loads booked to go to Belgium next week, following others that made their way there a few weeks ago. Otter is still keenly sought by craft ale brewers across the world, when we visited the maltings a couple of weeks ago we saw pallets stacked high with bags of malt destined for a retailer who sells brewing kits in Ohio in the US. Nearer to home brewers using Otter include the St Austell brewery (Tribute, Proper Job), Flack Manor brewery (Double Drop), Butcombe brewery (Butcombe Original).

There are other 1960s PBI crop varieties still being grown, Maris Piper spuds are still widely grown, we grew them here in our first venture into field scale spud growing in 2020. There is also a quality bread flour wheat, Maris Widgeon, still grown by some farmers, which is renowned for its long straw which is popular amongst thatchers.

The PBI’s prefix, Maris, which was first used in the early 1960s became known around the world. It actually owes its name to Maris Lane, which connected Trumpington High Street to Granchester in Cambridge.

When the decision was taken to privatise the organisation in 1987, the PBI and NSDO were together bought for £66m by Unilever, later sold on to Monsanto in 1988. But the UK Treasury had to forgo £38.8m of these total receipts because a far-sighted institute secretary, Denys Hadden had obtained charitable status for the PBI in 1968, so instead the money was ploughed into major improvements at the John Innes Centre when the ‘research’ side of the PBI was transferred to Norwich in 1990.

It’s a shame other organisations privatised at the same time hadn’t had the foresight to protect themselves in a similar way, rather than allow their value to be shovelled down the throats of speculators and shareholders over the following 40 years, as we have seen with water, electricity, the railways and numerous others. Oops, how did that scurrilous slice of political comment sneak into an educational piece about malting barley…?

The malting process at Warminster is still very old fashioned, renowned as Britain’s oldest maltings, the newly delivered barley is first dried down to a consistent 12% moisture, then it is steeped in water tanks for 72 hours, during which time it is soaked and drained 3 times, so the grain is not drowned. After final draining the grain is spread out on the malting floors, where it stays for up to five days, where it will be turned normally twice per day, with a plough as demonstrated here by a keen volunteer, or with a machine which resembles an old fashioned lawn mower, it moves through the damp grain and flicks the grain in the air so as to ensure good airflow through the bulk of grain to encourage it to begin to germinate. As germination proceeds, enzymes turn the starch in the grain into sugar to feed the growing embryo.

At the point where maximum starch has been converted, the grains with their tiny roots on are taken to a kiln, where they are dried rapidly, the roots are rubbed off mechanically, then the malt is bagged and readied for sale. If you chew on a grain at this stage, you find it has a crunchy texture and a sweet malty taste, from maltose, the form of sugar that the yeast will feed on in the brew, to produce alcohol. Dissolve malt in water, add hops and yeast, and hey presto, you have made beer.

Since the beginning of February our heifers have been calving steadily, one of the bulls, Mr Red, was introduced to them several weeks ahead of the rest of the herd last May, for just 2 weeks. We were aiming for a 50% success rate from the 24 heifers, when scanned it turned out he had successfully served 21 of them, so our sheds are quite crowded. Pictured above is Ginge, the only red animal in the bunch, she has produced a lovely pair of twins, remarkable for a heifer, and she is doing them very well. We await the start of the main bunch, hoping there will be no more trouble of the kind experienced last week, when, after calving, one of the ladies popped out a prolapse. Fortunately there are no pictures of this unfortunate event, but the skill of our vet, armed with some sugar and a shot of oxytocin, and the perseverance of Dougal and Fred late into the evening saw all put back in order, mother and calf now doing well.

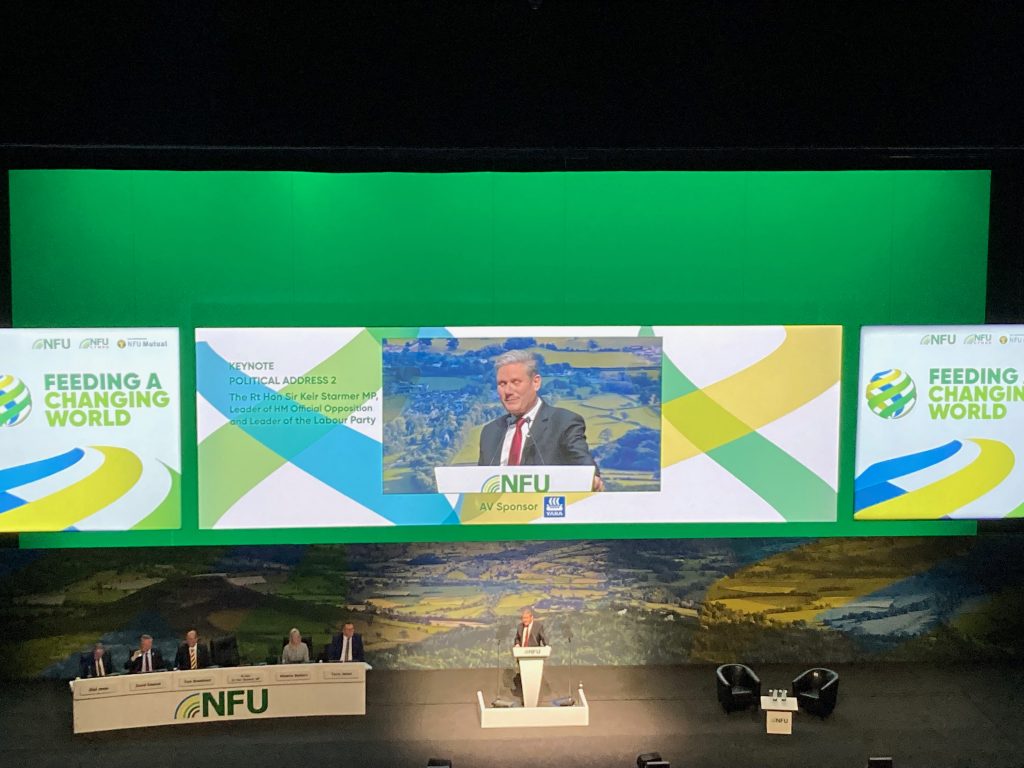

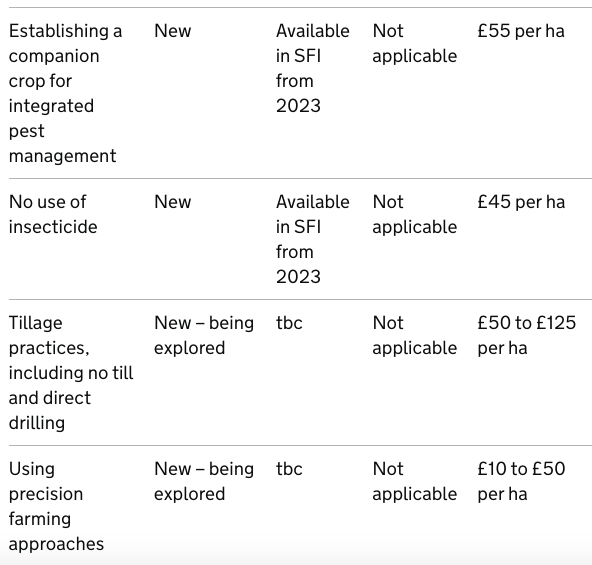

A trip to Birmingham earlier this week took in the NFU national conference, a two day extravaganza based at the International Conference Centre. A bit heavy on the politics this year, first up was Mark Spencer, Agriculture Minister, who spent some time once again explaining ELMS (the Environmental Land Management Scheme), there are many layers to this replacement for the flat rate (part of the EU’s common agricultural policy) Basic Payment Scheme (BPS) which has run since 2015, and rewards land holders simply on the basis of how much land they occupy. Some farmers have been getting impatient to see what ELMS will consist of, seeing as the BPS has been gradually reducing and will be down to zero by 2027. DEFRA have been taking their time, seeing as we’ve known something new would be required post Brexit for a number of years now, but there is no point rushing schemes out before they are ready, the history of British agricultural support is littered with the corpses of previous premature deliveries. There is hot debate surrounding several aspects of the SFI (Sustainable Farming Incentive), which is one of the three strands of ELMS, especially the hedgerow and grassland standards. On a very positive note, hidden amongst arable standards are proposed payments for farmers who do not use insecticides, the establishment of companion crops and for no-till crop establishment. We will be very pleased to take advantage of these options, which show that at least some departments within DEFRA are keeping themselves up to date with soil health and environmental issues.

We were addressed by Opposition leader Kier Starmer on Tuesday afternoon, who delivered a positive and slick speech. He fielded audience questions with good humour and navigated trickier subjects reasonably successfully, insisting that no doors will be closed, and that a Labour DEFRA will follow the science on tricky subjects like bovine TB. Hardly an assurance worth holding breath for though, when in their next breath they are talking about extending the Right to Roam, bearing in mind the horlicks the last Labour government made of this topic. Anyway, the best was kept for last, you cannot have escaped the story of how Secretary of State Therese Coffey bombed. I have never seen a conference performer behave in such a fashion, she was grumpy and rude, not very well briefed, and completely failed to engage with the room, let alone with Minette Batters, NFU president, who was her interviewer.

Aside from the politics, the conference is a great opportunity to network, catch up with old friends, and listen to wise and knowledgeable people exchanging experiences and sharing their thinking. Ash Amirahmadi, MD of Arla foods, buyers of milk from over 2000 dairy farmers in the UK, stands out as a beacon of hope amongst the leaders of our industry. Arla is a Danish-Swedish based co-operative owned by 9,700 farmers, and Ash explained how the company is taking its responsibility as a global food processor very seriously, particularly in how it is approaching net-zero policy, and climate-essential changes to the way we produce food. They are able to incentivise their producers to produce food in more sustainable ways by tweaking how they pay for milk.

Director General of the CBI, Tony Danker gave us insight into how he sees the greater economy reacting to government policy as it twists and turns. Then for a bit of blue sky thinking, we heard Prof Tim Benton, from Chatham House, say that food system transformation is needed to enhance human health, protect biodiversity, reduce climate impacts and build resilience, and that current government strategies will not achieve this change.

For light relief after all that, we were treated to an after dinner set by Impressionist Jan Ravens, of BBC Radio’s Deadringers, who crashed onto the stage as a convincing Liz Truss, and later closed her act by teaching the whole audience how to speak like Janet Street-Porter, it was very funny if you were there.

Beavers have been in the news again recently, farmers seem to be very good at getting worked up about them, worried that their land will be flooded, and trees will be damaged, and they are seemingly finding it hard to understand the good things the amphibious rodent can bring to the environment. It is true that if they are to be introduced, and they already have been in many areas including several sites in Dorset, then we ought to be allowed to manage them if their dam building threatens more harm than good. The government in its wisdom has made them a protected species, so their lodges, dams and the creatures themselves cannot be interfered with, and there is so far no sign of a protocol by which they can be managed. Beaver damage to trees has been seen near the Stour north of Sturminster Newton, and a beaver was filmed by a member of the public, in the river in Blandford last summer. To show beavers in action, mostly under cover of night, here is some video from Cropton Forest in north Yorkshire, where they have erected a dam 70 metres wide which is claimed to be reducing flooding risk to the town of Pickering. Local intelligence adds that work to erect a bund and a reservoir that holds 120,000 cubic metres of water, as well as over 100 leaky wooded debris dams may also have something to do with keeping the town flood free.

January 2023

Hedges have been taking up a lot of time and attention on the farm lately. Here is our cluster group a few weeks ago enjoying a talk from hedge specialist Sarah Barnsley from the Peoples Trust for Endangered species. We discussed many details of hedge management, from planting eg how many plants per metre, at what spacing, what mix of species, to the intricacies of trimming; annual, biennial, triennial, incremental, and at what point in the season. Later season cutting clearly leaves more fruit for the birds, especially on growth older than one year, but this poses a problem on wet land where farmers are usually keen to cut hedges early in the autumn before the land wets up then stays wet all winter. Later cutting means the hedge trimming tractor will make terrible ruts in soft ground. Then we moved onto laying and coppicing, which are necessary when the hedge has been allowed to grow up beyond trimming height, or the stems have become too thick for a flail trimmer. In an ideal world all our hedges would be on a long term rotation of laying or coppicing, gapping up, and two or three yearly incremental trimming for 15-20 years, until the laying can be repeated. At the point of laying or coppicing the hedge can produce a lot of logs for firewood, a valuable and renewable source of energy. I recently discovered how Ross Dickinson, a farmer in the Beaminster area, has made a successful business from doing just this. For a more detailed explanation have a look at this article in the Marshwood Vale magazine,

or to hear Ross explaining it himself, here is a link to a talk he gave to the Royal Forestry Society.

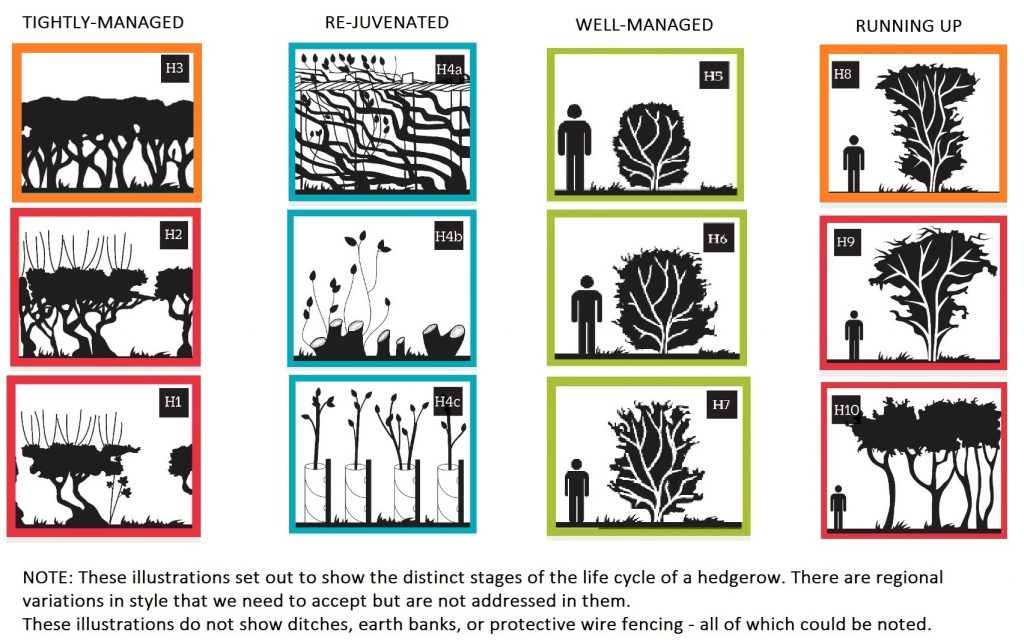

On the farm here we have hedges at all stages of condition, and after many years of flail trimming most hedges every other year, we are now planning on doing a quantity of laying and coppicing every year, aided where possible by our countryside stewardship scheme, which pays for a proportion of the costs involved. The first thing to do will be to assess every hedge and record its condition, and this can be made quite straightforward if assessments are based on the Adams scale, a series of diagrams of the stages of a hedge’s life which helps to assess it and suggests how to bring it back to useful condition, as conceived by Nigel Adams. https://hedgerowsurvey.ptes.org/hedge-management-cycle

The most difficult decisions usually involve the oldest hedges, which are often gappy and overgrown, some sections are shrouded in ivy, and are more a line of trees than a hedge. To bring it back to a useful hedge, that is, a condition to provide the best outcome for nature, generally means it needs coppicing (cutting off close to ground level). This sounds pretty extreme, but it is surprising how many of the mocks (stumps) will regrow the following year. We will then ‘gap up’ (fill the gaps between mocks) with new young trees (whips), protected from rabbits and hares by guards and supported by bamboo sticks, and then fence in the hedge on both sides to keep browsing animals at bay, eg deer, cattle and sheep. We have some stretches of very gappy hedge in prominent parts of the farm, which look fabulous when in flower in May, but are in truth gappy overgrown shrubs, with no bottom and little useful habitat for more than birds to perch and nest.

Should we bite the bullet, cut them off, gap them up and fence in, then look the other way for the next 5 years until they have grown back a bit? The reason we have hedges in this condition is that we have allowed them to grow to their natural shape, without trimming, for many years, and being mostly shrub plants, they eventually reach the end of their lives, and fall over. The best way to keep a hedge in shape is to periodically lay it, as Mr Dickinson says, every 15-20 years. This is less violent than coppicing, and preserves the right genetic material in the hedge, rather than importing new plants from elsewhere. Laying is slow and expensive, well suited perhaps, to the newly retired.

For the last 6 weeks, when the weather and pressure from other work has allowed, we have been planting new hedges, our ambitious plan in the stewardship scheme is to plant 1700m. The daft thing is that the rules in the 5 year countryside stewardship scheme dictate that all capital works, (as jobs of this nature are known) must be completed in the first two years of the scheme. We have asked many times why this cannot be altered to cover the whole 5 years, to spread the labour/time commitment. We did not get the go ahead for the new scheme until it was too late to plant much last year, so we are now left with a huge task to complete in a single season.

Fortunately we have been able to recruit willing, indeed keen, assistance, in addition to the always keen and hard working home team, so on many days we have had 6 or 7 on the job when it is not pouring with rain or frozen solid. We managed up to 190 metres planted and guarded on the best sunny day last week, the team divides into diggers, planters and stick/guarders, with occasional swapping around, progress has been impressive, even with very flinty ground in places. The job won’t be complete until the hedge is safely double fenced to keep out marauding animals.

Speaking of whom, the youngstock are progressing across our acres of carbon capture cover crops, sown after wheat back in September. The whole area was sown late as we were waiting for some rain before sowing, the bone dry seedbeds didn’t promise good germination. The consequence of late sowing is that the crops haven’t grown as much as we would hope in spite of the wet and mild autumn. The days get shorter, and sun lies lower in the sky. Good cover crops are a crucial part of trying to meet some of the ambition of regenerative farming, which aims to improve soil health and reduce reliance on artificial fert and chemicals; diverse well rooted crops growing in the soil at all times is the aim, and the incorporation of livestock should help too, the act of grazing stimulates plants into more growth, unless it is too cold. They can recycle a proportion of the plant material into manure that can be used by the next crop due to be planted in spring. The cattle are moved on daily, they get a hectare per day, and are always keen to move on when allowed.

On the wettest days they can make a bit of a muddy mess, but when the ground is frozen, they barely make a mark. We move them on quickly so as to leave enough greenery there to regrow if there’s a milder period of weather, such as over Christmas and early in January. Doug bought some handy fencing kit that allows you to pick up and move a large distance of fence on foot, the hand-held gadget holds the bundle of posts, and has a bracket and handle for winding the reel of wire in or out.

As a final thought, I recently heard that deforestation and land use change driven by agricultural expansion accounts for 13% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions, and commodities such as soya, beef, palm oil and timber are key global drivers. The UK’s own consumption of soya is inadvertently contributing to this picture with an estimated area of 1.7M ha of cropland required to meet the UK’s annual demand for soya. Widely fed to animals including cows, pigs and chickens, UK Soybean use represents 10.5% of Europe’s annual consumption of 30 million tonnes with 65% of the UK’s soya land footprint located in Argentina, Brazil and Paraguay, and 75% of global soya production is used in animal feed. A large proportion of soya is GM, and a significant amount is grown on land reclaimed from recently cut down rainforest.

Many UK arable farmers would be very happy to grow more legumes such as beans and peas, to replace the imported soya used by animal farmers. The protein levels in beans and peas are not as high as soya, and the money they earn all too often isn’t enough and the margin they produce is unexciting. However legumes in the arable rotation can add as much to the yield of the crop following them as a generous slug of fertiliser hence making them cheaper to grow. So perhaps we should be prepared to take a bit of a hit in arable margin, and protein buyers could perhaps consider not buying soya and clean up their conscience. Are we eating too much intensively raised food fed on imported feed that has a very high environmental cost attached?

HOT NEWS from DEFRA today, 26th January. The latest news is that amongst many other new options, under the new Standard of IPM (integrated pest management) in the Sustainable Farming Initiative programme, they are going to offer farmers £45 per ha to not use insecticide on our land. This sounds great, having eschewed insecticides 4 years ago, this should be an easy standard to meet. I wonder if they will back pay? At last a direct payment to persuade stop farmers doing something that causes widespread environmental destruction. You might think that a ban would be simpler, but there are many vested interests and people who deeply believe they can’t grow crops without such inputs. This incentive could actually be a more effective and less controversial route.

HOT NEWS: Defra released a number of new environmental offers for farmers yesterday, (Thursday 26th Jan) including a payment for farmers who spray no insecticide on their land, and another is promised for those who practise no-till. Does this mean we might be doing something right? Hard to believe that Defra might be getting the message about the environment, but not going to get too excited until we see the small print……..

December 2022

This picture demonstrates very clearly why we still keep a few sheep. In farming terms they are unproductive, they can denude a landscape with their persistent nibbling, they attract every ailment you can imagine, such as footrot, scab, and worms, they get hopelessly stuck on their backs in hot weather, they get stuck in brambles. Their wool, once the mainstay of our nation’s productive output, and despite its undeniable magical properties, is now a valueless annoyance which no-one has had the patience to breed out of them, and their meat, well if you can find any amongst the bones and fat then you are clever than I.

However, they make excellent pets. You can leave them outdoors all year round, they can survive on very little food and don’t drink much water, and you can turn up in the field with a group of tiny schoolchildren, where the sheep will gallop towards us, in search of titbits. Once the toast has been distributed most of the sheep wander off, but the best ones remain to entertain the children in the gentlest fashion. The children are mostly fearless, and the sheep reward their bravery with great patience.

This was the first time we have tried a school visit in December, lucky with a bright sunny, if cold, day, the children were well wrapped up and we had a lovely time exploring growing crops, we even found some worms, and we visited the cows, where 2244 wanted part of the action, here she is checking I have the trailer safely attached to the tractor. We finished off with a woodland walk and looked at bird food plots in the fields.

Further excitement followed in the sheep field a few days later when we introduced our new young crossbred ram Reggie. Professional sheep farmers may weep as they read this, however the paragraph above should have prepared them for this amateurish approach; No condition scoring, no careful breed selection based on feed conversion rates or growth rates, we simply found an attractive looking and fairly tame animal locally, (he has quite a bit of Suffolk in him), of a size who might be able to manage the job required of him, he was only born in March, and let him loose with a red raddle crayon attached. 5 red bottoms on day one and several more in the following days reassured us that he knew what he was doing. Fingers crossed that they don’t all return for more when we change to a blue raddle after 17 days.

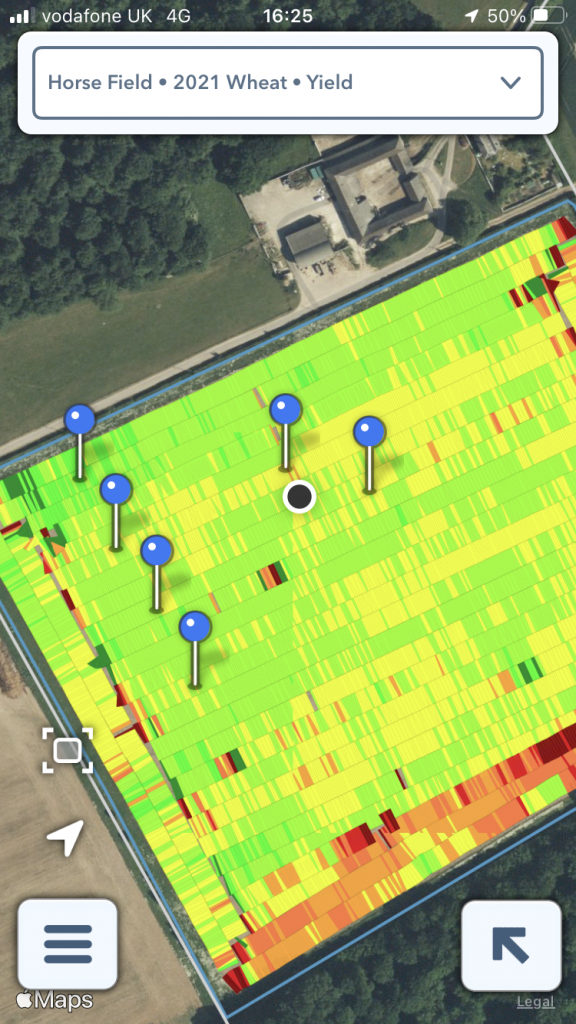

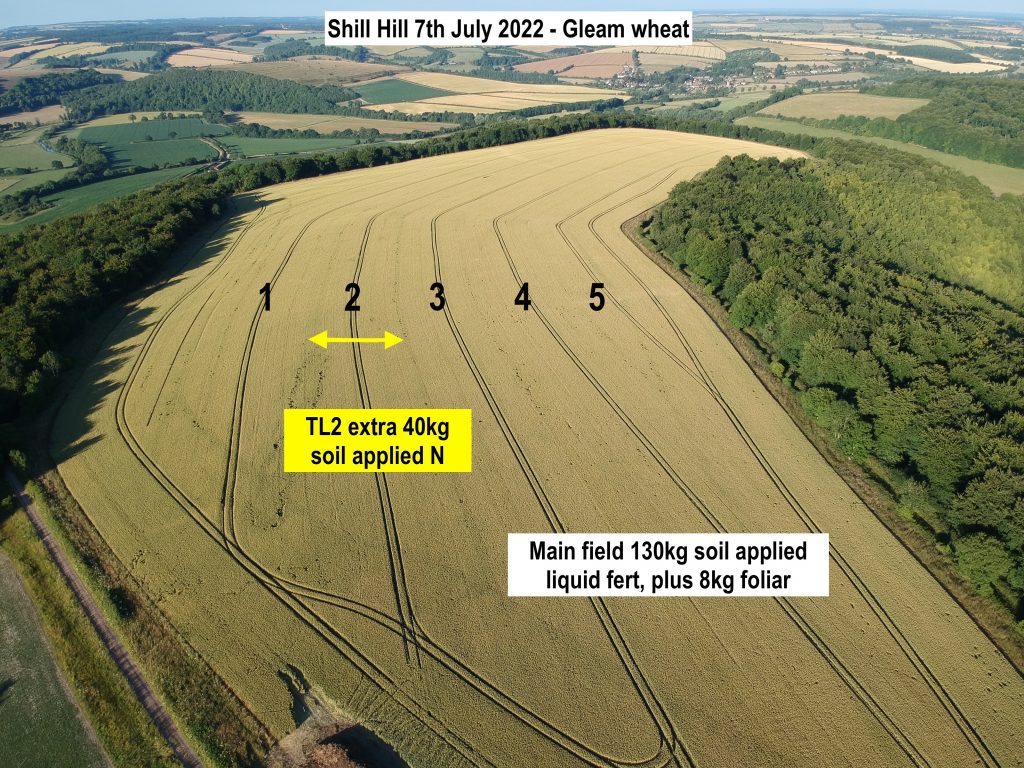

Here is a screenshot from a clever app which can help us to analyse the outcome of various tramline trials we carried out on this year’s crops. The yellow/green pattern represents the yield map generated by the combine whilst harvesting, green being better yield than yellow, with orange and red being progressively worse than yellow. The app, called ‘Climate Fieldview cab’ is from Bayer, one of the big agchem companies. Love them or hate them, they have the resources to put into developing clever stuff like this, not always just more chemicals.

The app allows you to select any area of the field you like, or individual passes of the combine, and it will then tell you the area and yield on that part of the field. So where we have applied a treatment to a particular part of a field, alternate tramlines in this case, we can then measure the effect of the treatment on yield. The blue pins represent where the tramlines are, I walked across the field and directly dropped each one in the right place as I crossed. This helps you to choose the right passes to include in the analysis, and to ignore the ones which run across two treatments. In this field we were testing a product which is supposed to reduce the amount of nitrogen lost to the atmosphere, by converting nitrogen oxide (NOx, potential pollutants) into plant feed. In this case we found no significant difference in yield between tramline treatments.

Elsewhere on the farm we wanted to test our nitrogen fertiliser policy on wheat, so we chose a single tramline in each of 4 different fields and applied an extra 40kg of nitrogen, then measured the difference using the app. We found that the extra 40kg produced extra yield between +5% and +8%. In 2021 a similar exercise increased yield from a minimum of minus 1% to +8%, here we used a difference of 50kg of nitrogen, with a higher base dose. If you have not already dozed off, you may now be asking “so what, it all depends on the value of grain and the cost of the fertiliser”, and you would be quite right. It also depends on when you sell the grain and when you buy the fertiliser, and whether you have to borrow the money to do so. A fair bit of number crunching and crystal ball gazing then needs to happen in order to decide the right approach for next season. We have already committed to buy next year’s fertiliser, at eye-watering prices. To leave it longer would have been reckless, we might not have been able to secure supply at all. So we are now very dependent on the grain price holding up to make the figures work and crop growing remain profitable. The trouble is that over the last 6 weeks the price of wheat has fallen £50 per ton, making a huge difference to predicted margins, so right now we are not looking so clever, (same as very many other farmers). Anyway we have the fertiliser in stock, though of course we don’t have to use it all if calculations suggest it won’t pay, we could hold some over for the following year, we have had to pay for it already though, a year before we will have a return from selling the grain it generates.

Welcome to the roulette wheel of farming. The old joke goes :How do you make a million from farming ? Answer: Start with two million. In some sectors like pigs, poultry and horticulture that is absolutely the case right now, with energy costs, labour shortage, and the intransigence of retailers leading to many producers saying “stuff this for a lark, I am not risking another production cycle when the prospects guarantee huge losses”, so they are not placing orders for new egg-laying chicks, productive sows are being slaughtered and not replaced, and the hort and protected (under glass) sector is reducing output after already two years of 30% crop being left unharvested due to lack of labour. The fear is that these producers don’t come back, and we throw ourselves ever more dependent on imported food supplies, which is the opposite to what many people say they want.

This picture illustrates part of the problem. Why does anyone need to import near identical products from overseas that we can produce here? Our production costs are higher even than Europe because of tighter welfare and other regulations, and we are now having to pay more for labour thanks to having become an unfriendly destination to foreign workers. So can anyone explain why we need to import Dutch, German or Danish pork loins? They are all the same price on the shelf. There only seems to be one likely outcome, answers on a postcard please. Or better, add a comment at the bottom.

We had a couple of days of intense cattle work last week, separating cows and calves, sorting groups away to different parts of the farm. The cows are now indoors on straw bedding, eating hay, and all the youngstock, two age groups, 86 animals, are all together on the first field of cover crop. They are getting a fresh hectare every day, the first week on the frost has worked well. Today is has started raining and it will be messy for a while, but hopefully the daily move will mean not too much damage to the soil.

November 2022

The season of mists and mellow fruitfulness is upon us, not to mention day after day of miserable dampness. After a soaking wet October, we launched into an equally wet November, 90mm in the first 10 days, and another 125 since then, in old money that’s 8 1/2 inches. Luckily we had sown the last of our wheat on the last day of October and it is up now and looking well, thank goodness we didn’t roll it. What is of more concern is the unseasonal mildness, by which I mean warmth. Why the term mild, this has been pretty extreme ? Our rape is full of phoma disease, the cereals are full of aphids, and the grass has barely stopped growing, so not all bad then.

Our cattle are still outside, but not for much longer now day length is reducing leading to a slow down in grass growth. Once the grass has been eaten it will be weaning time. The calves, now 9-10 months old, really should be able to cope without mummy now, and they will be moved onto the best of our cover crops. Having been sown so late we have been worried there wouldn’t be enough cover crop to sustain the youngstock through the winter, but the weather being as fickle is it is, has allowed quite a lot of catch up and there is a chance there will be enough. The year older group will also be heading for cover crop shortly, backed up with hay or silage. The cows will head for luxury indoor accommodation, bedded on straw with an under mattress of woodchip this year. Having coppiced some hedge last winter, and chipped the brash as the first step towards decomposition, a tip we learnt at the Groundswell event in the summer is to lay a base of wood chip beneath the straw in the cattle housing. Sitting throughout the winter soaked in cow pee should help it on the way to breaking down when added to a compost windrow next year. When straw or wood break down in soil, they need to absorb quite a lot of nitrogen, which is then not available for crop plants to use. If we can speed the decomposition with pee-innoculation prior to good composting, the end product should be that much more useful. Last season we built compost heaps in windrows of a size to fit a compost turning machine such as we saw at Groundswell. Our friend Jimi came along with his machine in August to show us what it could do, he worked his way through most of our heaps before the machine broke. It is usually difficult to get good decomposition of farmyard manure in a very dry year, but even just a single treatment with Jimi’s machine made a huge difference, we ended up with a pretty well rotted and friable product which was easy to spread evenly. We have put in a bid for a grant towards a compost turner for ourselves, as we can see this will be one way of improving our soils and at the same time reducing our dependence on artificial fertiliser.

Recent stories in the press about a revolutionary novel food that is being developed by a company in Finland are raising a few eyebrows, and with this in mind a small group of farmers arrived at the Electric Palace in Bridport last Saturday to join the throng queuing to listen to George Monbiot, campaigning journalist of some reputation. Bridport Literature Festival had engaged George to speak about the ideas in his book Regenesis, an extremely well researched demolition of livestock farming. Much of what he says rings true, eg problems in the River Wye catchment, and other UK rivers, as well as numerous issues related to intensive livestock systems around the world, however it is hard to listen to him when he effectively rubbishes organic, regenerative and extensive stock systems, because they use too much land.

He then produces with a flourish this protein dense bacterial miracle powder developed by a company in Finland called Solar foods, which only needs CO2 and electricity to grow, which it is claimed could feed the world from an area the size of greater London. After ranting about the power of corporate business (not to mention the NFU and DEFRA and how cosy they are) he then expects us to believe that this wonder food will not need to be ultra-processed and heavily invested in by big business in order to render it both edible and widely available.

Monbiot loves to blame farming for all our climate woes. I would be more sympathetic to him if he at least acknowledged that it is the amazing achievements of farming that have made us victims of our own success. We have grown enough food to enable us to support close to 8 billion people, growing by 80 million per year, this surely is where our climate problem really lies. As with all things the problem is demand driven, and without strict regulation the markets have conspired to produce enough food, cheaply enough, to get us to where we are. It is the environment, of course, which has suffered as a result, and we still haven’t put a proper value on that. Some would say the market should solve the problem. If the bacterial protein-rich goo is cheap and tasty enough people will buy it, and we old fashioned livestock producers will go out of business, or simply become a niche for rich people.

By chance we met him very briefly in the pub afterwards, but sadly he had no time to sit down and chew the fat with a quartet of livestock farmers…….. But he did agree to a selfie.

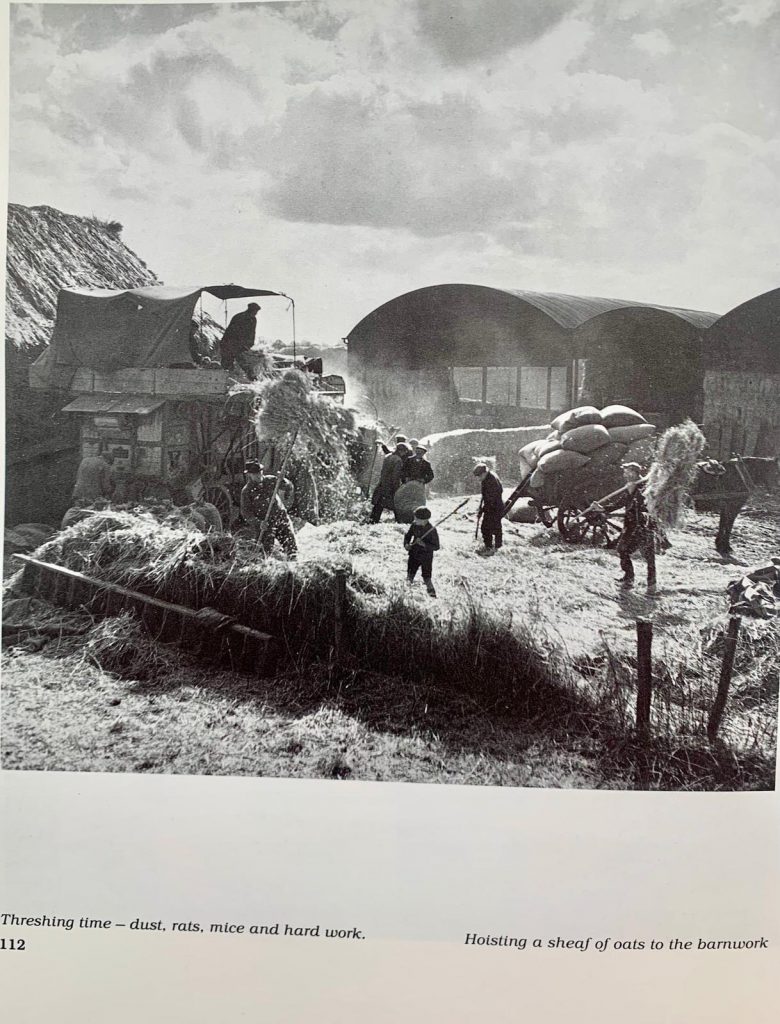

An interesting tale came to me from an old pal who has spent the last 30 years managing a large estate in Essex. Recently retired he now has time to appreciate the finer things in life, such as the rescue of a threshing machine that was closed up into a shed in Suffolk 50 years ago. It recently changed hands for £500, and the time came for it to be moved. The barn had to be half dismantled, then the machine was slowly extracted and loaded onto a lorry, to go to its new home where a few light repairs were made, and it was then put to work at Bardwell Windmill, still in Suffolk. The video shows that it rolled well on its wheels, which look sound, it may have been stored on blocks away from the damp. Amazing to see it back to work after such a long lay-off.

A lovely addition to the story, which comes from the same source, (thanks Alex), relates to the following picture:

“Picture of the same threshing machine working in the late 1940’s from a book on Essex agriculture. The boy trying to catch the mice on the stack was one of my senior tractor drivers when I took over at the Rayleigh Estate He told me that at the time the photo was taken there was a Department of Agriculture scheme that paid a few pennies per dozen mouse tails and that there was a “Department official” who came round on a bicycle to wherever the threshing machine was working and paid out the payment in cash. The young boys soon realised that after they had handed over the little bunches of mouse tails tied up in dozens and received their cash, that the Department man cycled off down the lane and as soon as he was out of sight he tossed the mouse tails over the hedge. The boys would wait in hiding where this usually happened and having collected the discarded bunches, would handed them in again the next day for more cash!”

October 2022

Fast becoming a regular on these pages, cow 2244 is quite a character, definitely boss of the bunch, one of our oldest and largest cows, 14 years old, here she is giving me a huge bellow in the ear, having just entered the field and struggling to get the gate shut before I was surrounded, she and her pals left me in no doubt that they felt it was time they were moved onto fresh pasture. However that kind of decision is above my pay grade, so I simply pointed out that there was still plenty of grass left and departed quickly.

Autumn sowing has proceeded at pace over the last 3 weeks, all is sown apart from 2 small fields of wheat, though the rain in the last 10 days has made the tail end a bit of an on/off affair, luckily Gary was close behind the drill with the rollers, so little remains unrolled. Rolling on stony land like ours is always best done in the autumn, essential to push flints below combine cutterbar height, leaving too much till spring is risky as once the ground has dried out sufficiently the crops are often too far advanced to roll. Direct drilling has again demonstrated how much more resilient it makes the job of sowing, in spite of numerous rain showers, the undisturbed soil drains quickly and we can press on after only a short delay, rolling is of course a different matter, and we have to be more patient. I am hesitant to mention the new season oilseed rape crop, it needs a little longer to determine whether all of it will see the season out, though may have turned the corner in the last 10 days, in spite of a slug and flea beetle onslaught. Sowing having been delayed by drought conditions in August, emergence coincided with the main beetle hatch, and although we have been trying to encourage predator insects with more flowery habitat, the crop has still suffered. Perhaps though, had we not established the extra habitat the crop would have failed completely. The flowery strips we have established in some of our larger fields have been part of the ASSIST project run by the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, who are trying to find out how far beneficial predator insects will travel into a crop in search of breakfast. One of their tricks is to place lumps of plasticine in the field, cunningly fashioned to look like slugs, and then after a day or two the ‘slugs’ are retrieved so that any bite marks on them can be examined and the potential predator identified.

We are in the first year of a new Countryside Stewardship agreement, and as well as the infield flowery strips, a significant part of it involves establishing 6m flower margins around the arable fields that don’t already have them. Many of our fields have had them in place since we first entered HLS (Higher level stewardship scheme) in 2010, when we used purchased seed to establish them. This time we have used our own seed, harvested this summer from a field of downland reversion created in 2010, as part of the original HLS, which itself had been sown with seed harvested from much older existing downland. It was on that occasion harvested by a seed specialist with a brush harvester and a tractor with very wide set wheels, on very steep banks. We cut this year’s seed with our own combine, it has now been analysed and 14 flower species have been identified, as well as a number of grasses. Fingers crossed for a good germination.

We bade goodbye to two old and faithful animal friends this year, both of whom were key players every time we have run school visits on the farm. At the end of a visit, after looking at growing crops, cows with calves, doing a woodland trail, and checking out shiny kit at work or parked up in the tractor shed, we usually finish with a visit to the paddock where the old pony and the tame sheep live, armed with a bag of toast, which is handed out to the children and immediately snatched from them by the greedy, though surprisingly gentle, sheep, and the pony if she is quick enough. Florrie the pony was allegedly 38 this year. Sadly 2022 was as far as she could manage, so too it was for Rocky, a wether lamb from 2012. Junior family members had lambed his mother on a Sunday morning in May of that year, he was a big fellow, and the birth proved too much for his mother, who did not survive, so my 12 year old daughter, once recovered from the shock of witnessing the ewe’s demise, gleefully brought him home to join that year’s band of orphan lambs. From that moment, a life of luxury and uselessness was assured. Last Sunday afternoon a walker informed us that there was a suspiciously dead looking animal lying on its side in the paddock. We had only moved them that morning, and Rocky had trotted along happily, so the end had come thankfully swiftly, lying peacefully in the autumn sunshine. RIP. Between them Florrie and Rocky must have met over 3000 children. That’s a lot of loaves.

The trials and tribulations of Rocky the sheep.

Poor old Rocky has had his share of troubles, first there was the time he got himself breached in the bushes, and had it not been for the eagle eye of Jayne, he would have expired there. Then there were the many episodes of the hole in his back. What had started with a small injury at shearing time turned into a massive issue once the magpies spotted it and got dug in before we noticed. First we tried disinfectant spray and Stockholm tar, but that just trickled away in the sunshine, then we tried a lady sheep’s prolapse harness, (the indignity of it), but from time to time he would shrug it off and the magpie was back in a trice, and the stupid animal would just let it peck away, ugh. After that we tried stitching a patch to his wool, knitting might have been better, but the wool was too short, and this didn’t survive trips into the bushes. Finally Nicki hit on the genius idea of the glue gun, a wonderful tool for a multitude of situations, the glued on patch lasted many weeks, enabling the wound to make a full recovery.

And finally……….. Some thoughts on ELMS

The ding dong over the future of ELMS (DEFRA’s environmental land management scheme) reached fever pitch a few weekends ago, some claim that it was initiated by dark arts specialists in the comms department at No 10, others pointed the finger at the recently ousted Goldsmith brothers, the keenest of environmentalists. Whoever it was, the leaked story was taken up by a journalist on the Guardian newspaper, it soon spread onto Twitter, and then all hell broke loose, even though the story was based on a fabrication. It stirred up both environmentalists and their adversaries alike, and the NFU (national farmers union) got badly caught in the crossfire. The NFU line on trying to balance food production with protection and enhancement of the environment has not changed, yet the leak implied that the NFU wanted ELMS to be halted. It took some time for the furore to die down, and the same journalist tried to resuscitate the story on the following weekend. Fortunately by then it was clearer what was happening and the NFU was able to push back with the full story.

The SFI, (sustainable farming incentive) is the wide ranging basic level of ELMS designed to attract many farmers into environmentally beneficial activity, the NFU is calling for it to be pushed ahead with vigour and to deliver 70% of farmers, with 65% of the ELMS budget, but DEFRA have not yet acknowledged that this is what will need to happen if it is to achieve what they say they want to achieve. ELMS is intended to be a partial successor to the BPS (Basic Payment scheme), a relic of the EU days, which is being reduced to zero in annual stages over 7 years. It is not pretended that ELMS will replace the BPS, but ELMS will offer farmers public money for providing public goods, in the shape of environmental enhancement. Supporting food production has been deemed less deserving of support with public money.

There are two other strands to ELMS, in addition to SFI: Local Nature Recovery, which is touted as the replacement for Countryside Stewardship, it could perhaps be wound in and simply emerge as an evolved version of CS, without the upheaval of a whole new scheme. Secondly Landscape Recovery, which needs to be handled with great care, it is likely to operate across a limited number of large areas where groups of landowners get together with a particular outcome in mind. 24 pilot projects were announced recently, which will each receive £500,000 to develop their projects. If this is likely to result in large areas taken out of food production then the potential environmental gain will need to make a very strong case.

The NFU is asking for a pause in broader ELMS development, in order to take full account of the changed situation across the world, the Ukraine war, the energy crisis, climate change and the ongoing aftermath of the covid pandemic, not to mention the consequences of brexit, which have all made a huge difference to food supply and flow around the world. If there is to be a pause in ELMS roll out in order to ensure that all these things reach fruition, then a delay in the reduction of BPS must also remain on the table.

We now know what SFI can look like in reality, for the two standards which are so far available (for arable and grassland soils). The interface is straightforward, the application is easy to complete online, though the level of funding may not be high enough. Let us hope that more standards will appear very soon, but they must be fit for purpose before release. Draft versions of a Hedgerow standard, for example, still need further work, a way needs to be found whereby SFI would fund farmers to plant new hedges in the advanced level. This could achieve much take-up and make a real difference. Hedges have the potential to provide huge environmental gain, but key will be the funding. The ‘Income foregone plus costs’ model that DEFRA is currently hooked on will not cover all the work needing to be done to many existing hedges, and if trying to get new ones planted, will be utterly insufficient.

10 years ago on the hill. Worth a look this month, the aftermath of THAT wet summer…..