The View from the hill 30th April 2023

Suddenly spring is here, though not exactly convincingly. While we’ve been spending too much time indoors because it has still been cold and wet through much of April, everything outside has been getting on with it in spite of the weather. Many farmers have been complaining that the grass isn’t growing fast enough for them to be able to let their animals out of their winter quarters, and others say the ground has been too wet and bovine feet will turn everything to mud in a flash, but there is no denying that things are indeed growing, like this lovely patch of wild garlic and bluebells together next to the river Stour just upstream of Durweston. We are just about at peak spring flowers now, and it is essential to get out and enjoy them. Bluebells are always a joy to brighten a dull day or mood, and an unbroken carpet of garlic, as there is in one or two local woods, is like a fresh fall of snow, though considerably smellier, which one barely dares spoil with a footprint.

Here are some cowslips that just get better and better every year, on a 10 acre field which we reverted to downland under stewardship, in 2010, using seed harvested from the flowery steep banks nearby, the flowers have improved as the fertility has depleted, meaning the grass gets less competitive allowing the flowers to proliferate. There are many species here, including a few orchids, and if we manage the livestock grazing correctly, allowing the flowers to set seed and spread each year, their coverage improves.

The earlier calving cows, and their calves, which were born from the beginning of February onwards, have been out of doors for a few weeks on drier fields, the calves are growing really well, and the cows are slowly filling out after their winter hay diet of the last 5 months. We just need for them to shed the remnants of their scruffy winter coats, and start to shine, then they will look a whole lot better.

This year’s 6 new heifer entrants to the herd were introduced to Mr Red last week, but they didn’t seem to know quite what to do with him. He will be with them for the next 3 weeks, then he will be let loose with a larger group of the older cows for around 9 weeks. Theo the (red) Hereford will take care of the other group. The purchase of these two new bulls last year, both red in colour, has proven to be a great success, we now have a lovely crop of multi coloured calves, with more variation from Theo than from Mr Red, (Angus) who carries the recessive red characteristic. Readers who were paying attention last month, and who have at least a rudimentary understanding of genetics, will recall that although red in colour, he is an Aberdeen Angus, where the most common, and dominant, gene carries black colouring. Most of the cows and heifers that Mr Red served last year are at least ¾ black Angus, so many of his calves have come out black. However of note are the twins belonging to Ginge, our one red heifer from last year, which are a gorgeous red. Pictured here at Websley when they were smaller.

One fine day 2 weeks ago, we made the tricky decision to get on and shear our tiny sheep flock. We found a very good shearer, Mike, locally, who came along to shear our pregnant ewes with care and precision, very few were nicked in the process, and all looked very smart after their trim. There were a few cold nights following, so they were allowed to sleep in a barn overnight, we didn’t want anyone going into premature labour from environmental shock. We are now waiting patiently for the arrival of some lambs, hopefully starting around May 5th. At shearing time we convinced ourselves that they are all pregnant, which is a significant improvement on last year. The ewes are now back in the paddock nearer home where it is easy to keep an eye on them.

There is little doubt in my mind that when a ewe looks like this, there is a good chance she is carrying at least one lamb.

Whilst on livestock, it wouldn’t be right to omit mention of this year’s trio of piglets, who arrived around 3 weeks ago. Greedy as always, the weather has made it very easy for them to turn their paddock into a ploughed mess far quicker than their predecessors of the last 3 years, when we had very dry spring weather and the soil was far less pliable.

They come from a farm near Milton Abbas, where Maureen Case runs a small pedigree herd of Oxford Sandy and Black pigs, with 7 sows and 2 boars. These three gilts came from the same litter, they were 9 weeks old when we picked them up.Here is another (younger) litter, of 11, it turns out that there is always a runt of the litter, the big ones bag the more milky teats at Mum’s front end, and the smaller ones have to make do with the smaller yield of the rearmost teats. The big piglets get bigger and stronger, not for a moment concerned with the welfare of their smaller siblings. Watching ours when we feed them, one is reminded why they are called pigs, ear biting and barging is commonplace in order to secure the largest portion of the ration. One of ours was clearly a front end guzzler, she is bigger than the other two and doesn’t hold back.

The Blackthorn winter has certainly lived up to its name this year, much of April has been cold, and the Blackthorn has flowered vigorously for a long time, hopefully that will mean plenty of sloes for next autumn. Blackthorn is an important host of the Brown Hairstreak butterfly, which lays its eggs on young blackthorn twigs, the caterpillars hatch and remain on the blackthorn for much of the year, before eventually emerging as a handsome butterfly with a dark upper wing surface, and a contrasting orange underside. Over-zealous hedge trimming can eradicate populations alarmingly easily, but once we have learnt this kind of fact, farmers are usually keen to help, and soon grasp the importance of every other year trimming, or longer term hedge management incorporating coppicing or laying, often supported by environmental schemes, which pay farmers to adopt beneficial practices.

As the blackthorn flowers fade, we find the hawthorn is in bud and will very soon deal us another beautiful snowy blanket along many of our hedges and bushes.

I got very excited a couple of months ago when I discovered that a farmer friend I knew from the Tisbury area was as a sideline importing and propagating Dutch elm disease-resistant Elm Trees. Ancient maps of the Durweston area show trees in clumps in several of our fields, which I feel sure would have been elms. Back in the 80s I remember digging out the remains of huge tree stumps from our meadows near the old Durweston mill. At the time we believed these to be Elms, the last of the great many that used to populate the countryside before Dutch Elm disease laid waste to them. The disease is caused by the fungus Ophiostoma novo-ulmi which is spread by elm bark beetles. It got its name from the team of Dutch pathologists who carried out research on the diseases in the 1920s. Ash dieback disease now threatens another mainstay tree of the English landscape, the sight of hundreds and thousands of ash trees succumbing to the disease is enough to reduce one to tears of sadness and frustration. Anyway, in an attempt to remain positive, this story is about the efforts of a small number of dedicated plantsmen to try to resuscitate the English Elm. There has been work in universities across the world to develop resistant elms and these hybrids are subjected to inoculum trials to assess their resistance to Dutch elm disease.

While these resistant strains look similar to English varieties of elm, they are described as exotic species. They might not perform exactly the same ecosystem function so replacing elms with them is not necessarily a complete solution. My farmer friend had a small stock of a cloned variety called Lutece available, which has become the most widely planted of the modern hybrids in Britain, through the efforts of Butterfly Conservation and the Island 2000 Trust on the Isle of Wight. Sadly its extended dormancy in spring may prevent it from becoming the resource for the White-Letter Hairstreak butterfly that it was once hoped to be. In our case, the 9 specimen trees that Peter supplied are all budding up nicely, and I am hoping to obtain more next winter so as to be able to complete a line of them along the road between Durweston and Bryanston. For further information please have a look here https://resistantelms.co.uk/elms/ulmus-lutece/, or here https://www.woodlandtrust.org.uk/trees-woods-and-wildlife/tree-pests-and-diseases/key-tree-pests-and-diseases/dutch-elm-disease/

There is a lot of debate surrounding the original appearance of the Elm in Britain, and its subsequent development, generally it is not a strong breeder, and very often spreads by suckers rather than seed, perhaps this made it more vulnerable to disease? Further interesting debate here https://www.wildlifebcn.org/sites/default/files/2021-07/Complete%20key%20to%20native%20and%20naturalised%20elms.pdf

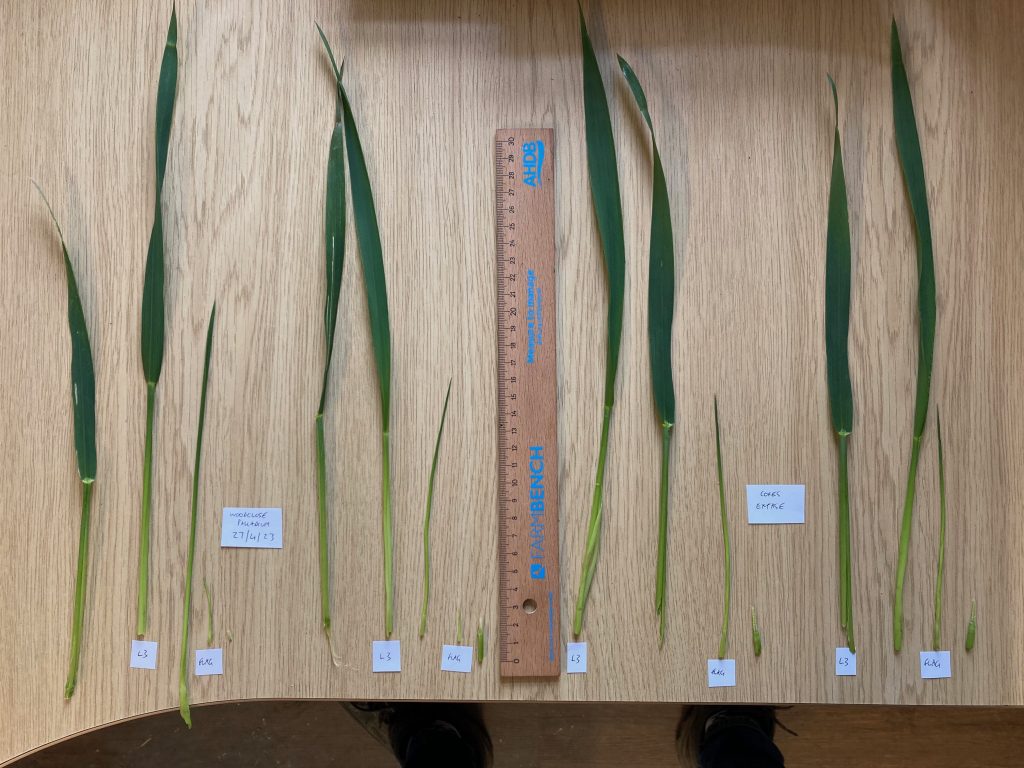

Some dissected wheat plants from last week, showing development stages, this helps us to decide when is the best time to deploy fungicides or other products to help the plants fend off disease. The first key timing is when final leaf 3 is fully emerged, this leaf makes a small but significant contribution to final yield, and by keeping it clean, we can help slow the spread of disease to the uppermost leaves, especially the flag leaf, which can contribute as much as 50% of crop yield. You may be able to see from the picture that the variety on the left, Palladium, is some way behind the Extase on the right. Extase is an early developer, and therefore a good indicator as to the likely growth stage of all the wheat in a given season. The flag leaf, once fully emerged, is therefore the most important target for expensive inputs. This year we are trying out products to boost the plants own defences against disease, as well as carefully deployed fungicides, which have become eye-wateringly expensive. Our policy of choosing varieties with the best resistance ratings against disease, combined with a reduction in rates of fertiliser, should reduce disease pressure, and the application of silicon and salicylic acid are aimed at boosting plant defences, rather than simply attacking the fungal crop diseases with fungicides, which could be counter productive when we are also trying to encourage fungal growth in the soil. Mycorrhyzal fungi in the soil are intimately incorporated with plant roots, and are essential for conveying sugars (carbon) from plant photosynthesis, into the soil, as well as for sourcing minerals from the soil to feed into the plants, too much fungicide can impede these processes.

In a further attempt to reduce our reliance on fertiliser and chems, we are trying out bi-cropping, in this case, growing spring wheat and beans together, reducing the risk of disease for both crops, and contributing diversity to the soil and environment. Once harvested we will attempt to separate the wheat and beans with our ancient cleaner. They are being grown on contract with a company called Wildfarmed who encourage growers to try more environmentally friendly farming methods by finding premium markets for the produce. https://wildfarmed.co.uk

Ooh the bean and wheat combination looks interesting. I wonder how carlin peas and wheat would get on?

excellent as always

Aspirin for wheat! – salicylic acid (approximately). Terrific read George, thank you.

Went straight to junk this month so no early comment George, only just found it.

I now feel educated and informed and not a little entertained, thankyou.

Really enjoyed reading this George.

The cold wet spring seems to have compressed the bluebell season, as some woods are now in full leaf with bluebells yet to fully open.

I’m very interested in the Wildfarmed wheat, and whatever its protein % would be very happy to put some of it through its paces – either sourdough or yeasted.