Hedges have been taking up a lot of time and attention on the farm lately. Here is our cluster group a few weeks ago enjoying a talk from hedge specialist Sarah Barnsley from the Peoples Trust for Endangered species. We discussed many details of hedge management, from planting eg how many plants per metre, at what spacing, what mix of species, to the intricacies of trimming; annual, biennial, triennial, incremental, and at what point in the season. Later season cutting clearly leaves more fruit for the birds, especially on growth older than one year, but this poses a problem on wet land where farmers are usually keen to cut hedges early in the autumn before the land wets up then stays wet all winter. Later cutting means the hedge trimming tractor will make terrible ruts in soft ground. Then we moved onto laying and coppicing, which are necessary when the hedge has been allowed to grow up beyond trimming height, or the stems have become too thick for a flail trimmer. In an ideal world all our hedges would be on a long term rotation of laying or coppicing, gapping up, and two or three yearly incremental trimming for 15-20 years, until the laying can be repeated. At the point of laying or coppicing the hedge can produce a lot of logs for firewood, a valuable and renewable source of energy. I recently discovered how Ross Dickinson, a farmer in the Beaminster area, has made a successful business from doing just this. For a more detailed explanation have a look at this article in the Marshwood Vale magazine,

or to hear Ross explaining it himself, here is a link to a talk he gave to the Royal Forestry Society.

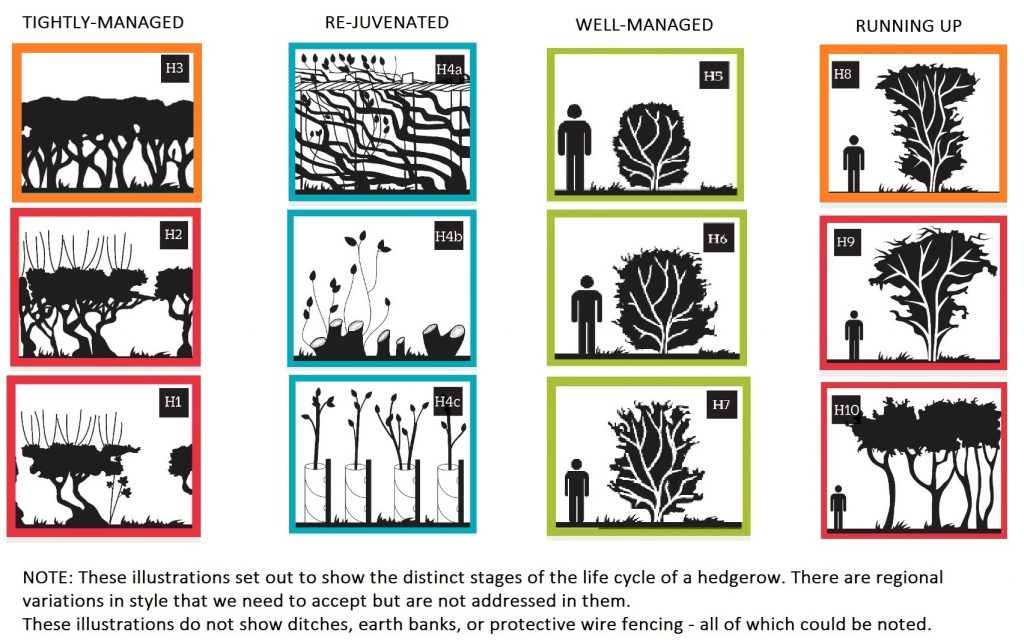

On the farm here we have hedges at all stages of condition, and after many years of flail trimming most hedges every other year, we are now planning on doing a quantity of laying and coppicing every year, aided where possible by our countryside stewardship scheme, which pays for a proportion of the costs involved. The first thing to do will be to assess every hedge and record its condition, and this can be made quite straightforward if assessments are based on the Adams scale, a series of diagrams of the stages of a hedge’s life which helps to assess it and suggests how to bring it back to useful condition, as conceived by Nigel Adams. https://hedgerowsurvey.ptes.org/hedge-management-cycle

The most difficult decisions usually involve the oldest hedges, which are often gappy and overgrown, some sections are shrouded in ivy, and are more a line of trees than a hedge. To bring it back to a useful hedge, that is, a condition to provide the best outcome for nature, generally means it needs coppicing (cutting off close to ground level). This sounds pretty extreme, but it is surprising how many of the mocks (stumps) will regrow the following year. We will then ‘gap up’ (fill the gaps between mocks) with new young trees (whips), protected from rabbits and hares by guards and supported by bamboo sticks, and then fence in the hedge on both sides to keep browsing animals at bay, eg deer, cattle and sheep. We have some stretches of very gappy hedge in prominent parts of the farm, which look fabulous when in flower in May, but are in truth gappy overgrown shrubs, with no bottom and little useful habitat for more than birds to perch and nest.

Should we bite the bullet, cut them off, gap them up and fence in, then look the other way for the next 5 years until they have grown back a bit? The reason we have hedges in this condition is that we have allowed them to grow to their natural shape, without trimming, for many years, and being mostly shrub plants, they eventually reach the end of their lives, and fall over. The best way to keep a hedge in shape is to periodically lay it, as Mr Dickinson says, every 15-20 years. This is less violent than coppicing, and preserves the right genetic material in the hedge, rather than importing new plants from elsewhere. Laying is slow and expensive, well suited perhaps, to the newly retired.

For the last 6 weeks, when the weather and pressure from other work has allowed, we have been planting new hedges, our ambitious plan in the stewardship scheme is to plant 1700m. The daft thing is that the rules in the 5 year countryside stewardship scheme dictate that all capital works, (as jobs of this nature are known) must be completed in the first two years of the scheme. We have asked many times why this cannot be altered to cover the whole 5 years, to spread the labour/time commitment. We did not get the go ahead for the new scheme until it was too late to plant much last year, so we are now left with a huge task to complete in a single season.

Fortunately we have been able to recruit willing, indeed keen, assistance, in addition to the always keen and hard working home team, so on many days we have had 6 or 7 on the job when it is not pouring with rain or frozen solid. We managed up to 190 metres planted and guarded on the best sunny day last week, the team divides into diggers, planters and stick/guarders, with occasional swapping around, progress has been impressive, even with very flinty ground in places. The job won’t be complete until the hedge is safely double fenced to keep out marauding animals.

Speaking of whom, the youngstock are progressing across our acres of carbon capture cover crops, sown after wheat back in September. The whole area was sown late as we were waiting for some rain before sowing, the bone dry seedbeds didn’t promise good germination. The consequence of late sowing is that the crops haven’t grown as much as we would hope in spite of the wet and mild autumn. The days get shorter, and sun lies lower in the sky. Good cover crops are a crucial part of trying to meet some of the ambition of regenerative farming, which aims to improve soil health and reduce reliance on artificial fert and chemicals; diverse well rooted crops growing in the soil at all times is the aim, and the incorporation of livestock should help too, the act of grazing stimulates plants into more growth, unless it is too cold. They can recycle a proportion of the plant material into manure that can be used by the next crop due to be planted in spring. The cattle are moved on daily, they get a hectare per day, and are always keen to move on when allowed.

On the wettest days they can make a bit of a muddy mess, but when the ground is frozen, they barely make a mark. We move them on quickly so as to leave enough greenery there to regrow if there’s a milder period of weather, such as over Christmas and early in January. Doug bought some handy fencing kit that allows you to pick up and move a large distance of fence on foot, the hand-held gadget holds the bundle of posts, and has a bracket and handle for winding the reel of wire in or out.

As a final thought, I recently heard that deforestation and land use change driven by agricultural expansion accounts for 13% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions, and commodities such as soya, beef, palm oil and timber are key global drivers. The UK’s own consumption of soya is inadvertently contributing to this picture with an estimated area of 1.7M ha of cropland required to meet the UK’s annual demand for soya. Widely fed to animals including cows, pigs and chickens, UK Soybean use represents 10.5% of Europe’s annual consumption of 30 million tonnes with 65% of the UK’s soya land footprint located in Argentina, Brazil and Paraguay, and 75% of global soya production is used in animal feed. A large proportion of soya is GM, and a significant amount is grown on land reclaimed from recently cut down rainforest.

Many UK arable farmers would be very happy to grow more legumes such as beans and peas, to replace the imported soya used by animal farmers. The protein levels in beans and peas are not as high as soya, and the money they earn all too often isn’t enough and the margin they produce is unexciting. However legumes in the arable rotation can add as much to the yield of the crop following them as a generous slug of fertiliser hence making them cheaper to grow. So perhaps we should be prepared to take a bit of a hit in arable margin, and protein buyers could perhaps consider not buying soya and clean up their conscience. Are we eating too much intensively raised food fed on imported feed that has a very high environmental cost attached?

HOT NEWS from DEFRA today, 26th January. The latest news is that amongst many other new options, under the new Standard of IPM (integrated pest management) in the Sustainable Farming Initiative programme, they are going to offer farmers £45 per ha to not use insecticide on our land. This sounds great, having eschewed insecticides 4 years ago, this should be an easy standard to meet. I wonder if they will back pay? At last a direct payment to persuade stop farmers doing something that causes widespread environmental destruction. You might think that a ban would be simpler, but there are many vested interests and people who deeply believe they can’t grow crops without such inputs. This incentive could actually be a more effective and less controversial route.

HOT NEWS: Defra released a number of new environmental offers for farmers yesterday, (Thursday 26th Jan) including a payment for farmers who spray no insecticide on their land, and another is promised for those who practise no-till. Does this mean we might be doing something right? Hard to believe that Defra might be getting the message about the environment, but not going to get too excited until we see the small print……..

Yes, hopefully good news from Defra. No insecticides is a no brainer for me too.

I haven’t waded through the full details yet as there is a mountain of information there, it is supposed to be simple but I am not convinced that an expensive specialist won’t have to be called in by me to translate it.

I use a small amount of soya on my farm, I have tried to use home grown beans and lupins but both cannot be included at high enough proportions in the pig ration to give the pigs enough protein to grow properly due to other things in the beans causing gut problems.

I think it unlikely we can adjust the animal diet, soya to local legume, without adjusting the breed of livestock we rear which in turn might well mean adjusting our food tastes and trends. It has been done before. Refined carbohydrate and sugar is fast overtaking fat as the culinary bogey man so the obsession with lean (flavourless) meat might be waining; pork and beans, pork and beans.

I notice that new hedging seems to be planted very densely. I would suggest that a minimum of 70cm between the rows and 140cm between plants, reducing competition, would make for a better hedge in the longer term, especially if laying is part of the management.

It’s all about the RPA regs. If you want the grant assistance you have to obey the rules. Maybe pig farmers don’t have such worries…….

Many hedgerow trees are species which can remember aurochs and elephants, creatures who periodically smashed the trees to pieces. In doing something similar we only mimic nature, though a tidy hedge was never left by a mammoth.

Looking forward to see if options can be stacked in the environmental offer, but looks promising.

Should our Govt simply ban imported soya?

Great read as always George..

I am not a fan of banning things without a thorough plan to mitigate the problems that might cause. By all means put measures in place that will change behaviour over time (Carrot and Stick) but some well intended interventions simply cause an alternative that has other negative consequences. I like the direction of travel that is being indicated by these new measures, we must encourage farmers to engage with them positively.