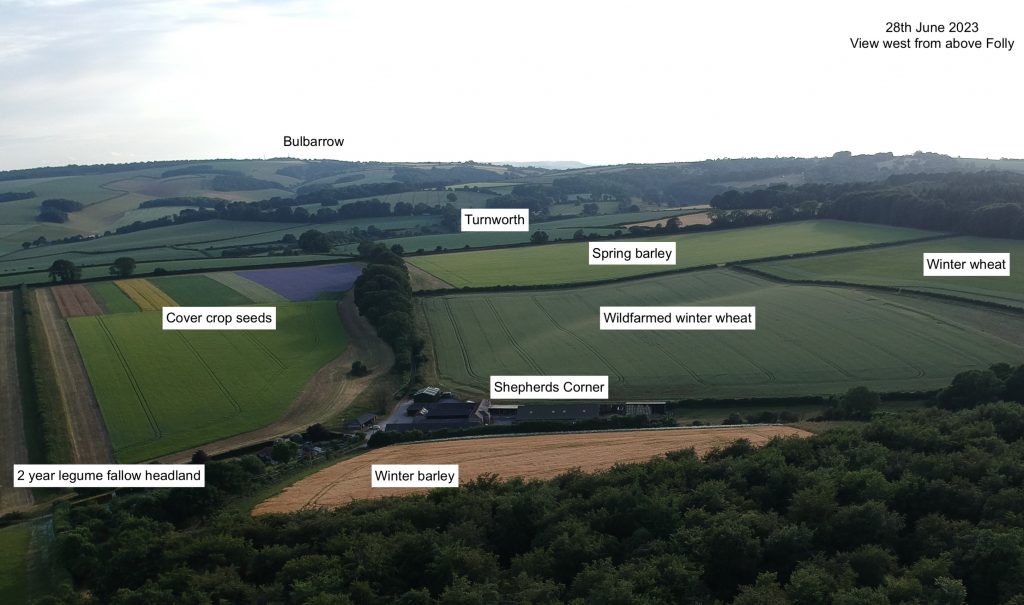

The View from the Hill

Who in all honesty can tell a frog from a toad? Our neighbours’ pond has recently been a hotbed of rampant reproduction, libidinous croaking has filled the air at all hours of the day and night, and now the pond is brimming with spawn, ready to erupt into a myriad tadpoles in a few weeks’ time. But how to know if we are witnessing Toad or Frog rumpy? The guide books are not terribly helpful, they seem to assume that you have a frog in one hand and a toad in the other, so that you can compare the sliminess of their skin, the pointiness of their facial features, or the length of their legs, but in reality how likely is that to happen? What did it for us was the simple fact that toads lay their spawn in lines, and frogs do it in clumps, and as you can see clearly in the picture, what we have is huge clumps, along with a great many froggy parents, with one (pointy-faced) individual standing guard. This simple method of identification soon falls apart outside of breeding season, by which time you will have had time to catch one of each and do a thorough examination.

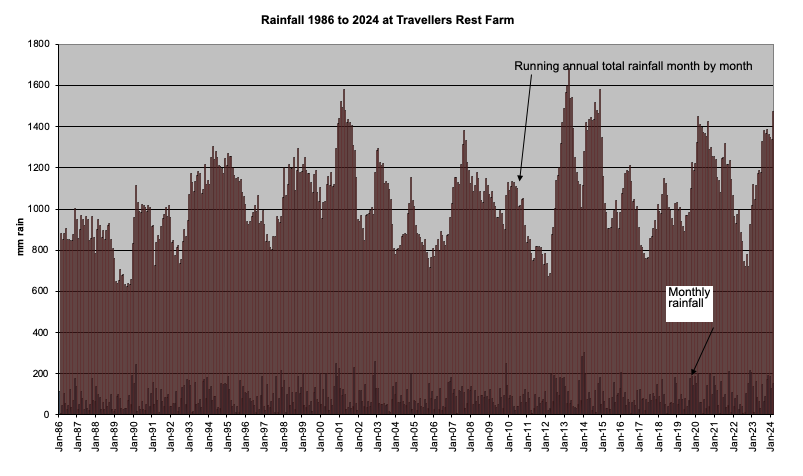

There was an article somewhere recently which blew a big hole in the old argument that we Brits are boring because we spend all our time discussing the weather. The theory holds that discussion of the weather is what binds us together, it never fails to engender a response from the person you address about it, one can share the pleasure of a sunny day, or commiserate about endless gloom. The weather affects what you are going to wear, it can dictate the entire shape of the day ahead, especially if you are a farmer, it is also likely to affect what you will eat today. So let’s celebrate it, while I dribble out a few weather stats. This may well feel like the wettest winter in many years, in fact it is only the third wettest in the last 12 years, both 2013-14 and 2019-20 were wetter from October to February. However that said, the rainfall we have endured in that 5 month period represents 75% of the 39 year annual average total (1100 mm). Does that mean we are heading for a dry period? Looking at the long term 12 month trend on this graph, it looks like we could be about to peak, but it could go anywhere. There’s lies, damned lies, and statistics……

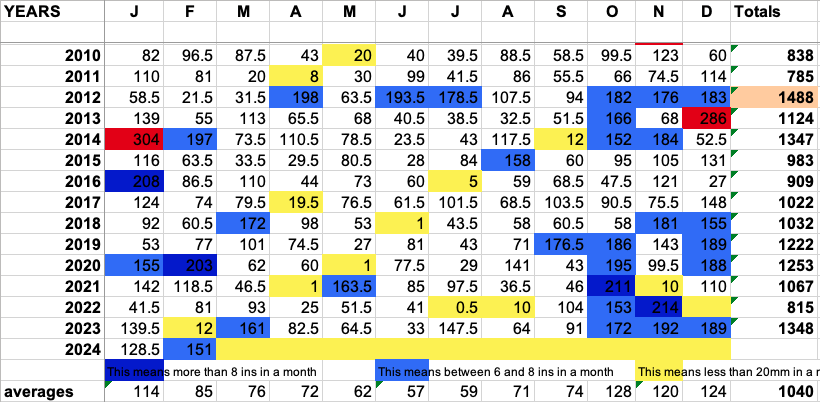

For the geeks, here are the numbers for every month since 2010.

Last week saw the dreaded annual TB test, which cattle and humans dread in equal measure. On Monday our vet arrived to find all the cattle arranged and waiting for him. He has to trim off some hair, measure the thickness of the skin, and then inject two vaccines into the skin of the neck of the animal. He then returns after three days to ‘read the lumps’.

The lower vaccine site is a mix of proteins extracted from cultures of mycobacterium bovis which has been killed by heat, and the upper site is a dose of avian tuberculin, which acts as a kind of control, representing as it does naturally occurring tb in the environment. The skin test can be interpreted at either standard or severe interpretation. Standard interpretation is the default used for all routine surveillance testing, whilst severe interpretation is used in circumstances where TB is strongly suspected or confirmed e.g. for testing in TB breakdown herds.

Where there is any detectable reaction at either site, both sites are re-measured with callipers and the measurements and type of reaction recorded against the animal, along with the test result after interpretation.

The size and nature of any reactions at the avian and bovine injection sites are measured and compared. Depending on the degree of reaction to the skin test and the interpretation of the test, the animal is classified as;

Clear – negative result

Fail – reactor or positive result

Inconclusive reactor (IR) – the animal shows a reaction to bovine tuberculin greater than the avian, but not strong enough to be classified as a reactor. IRs must be isolated and re-tested after 60 days. Animals that have an inconclusive result at two consecutive skin tests are considered reactors.

We have managed to get our herd onto a health pathway that entitles us to annual TB testing, rather than the previous 6 monthly, unless you are shut down. The outcome of last week’s test was that a single animal tested as an Inconclusive Reactor, which is almost worse than a full reactor. A full reactor will be taken for destruction by DEFRA, and compensation will be paid, whereas an IR can either be destroyed with no compensation, or kept for a second test at 60 days. If it fails again, it is regarded as a reactor and the whole herd will have to pass two further clear tests at 60 day intervals, if it passes it can return into the herd and be declared clear. However its presence will prevent the herd’s return to higher health status and therefore will be denied annual testing, instead having to undergo 6 monthly testing, which all points towards the animal taking a short journey to heaven as the least worst option.

The stress of TB testing on man and animal is immense. However well we set up the handling system to gently encourage the animals into the crush, and however calmly we handle them for the rest of the year, the animals know when it’s testing day, they can smell the vet a mile off and know that he or she is going to stick needles into them which sting.

Why we are still having to undergo this archaic and inhumane system to manage a disease is quite bewildering. How did we manage to design and build the covid vaccine and stick it in the whole human population in no time at all, and yet still be told that a TB vaccine for cattle always seems to be 5 years away?

A huge amount of effort has gone into reducing the reservoir of TB in wildlife, in Dorset in particular new outbreaks of TB in herds have reduced by well over 50% since the beginning of the campaign to control badger numbers in 2016. That’s a huge improvement, but the cull is being drawn to a close, with small trials being undertaken to evaluate the effectiveness of vaccinating badgers, which is hard to see having a significant benefit, and certainly will be wildly poor value for money.

The problem can’t all be laid at the badger’s door however, there is clearly still a reservoir of disease in the cattle population, the testing regime doesn’t seem to be able to root out all animals carrying the disease subliminally. So there they remain, slowly drip feeding it into their fellow cows. To be quite honest, until there is an effective vaccine, the near future lies largely in farmers’ hands, the chances of avoiding TB will only be able to improve if farmers practise the following:

- Operate closed herds (ie no imports of live cattle from other farms anywhere)

- Co-operate with APHA (animal and plant health agency) to use all tests available to clear out the disease from herds

- Reduce to zero the opportunities for cattle to interact with wildlife. This is hugely difficult, especially when grazing outdoors.

- Keep a close eye on numbers and activity of wildlife

- If all these cannot be achieved then consider giving up cattle farming.

This is admittedly brutal, and a personal view, with huge implications for very many farmers’ business models, but without all of the above, in the absence of an effective vaccine, we are simply destined for more of the same.

Tales from the shearing shed

Six weeks as Rousies with a shearing gang in New Zealand has been a great experience for two Reading University graduates through December and January. The main job is to move the wool from the shearer to the packer as the sheep are stripped of their wool, sorting out any dags (bits with poo on) along the way. With up to 6 shearers working flat out on the biggest flocks, the best of them shearing 400 or even 500 per day, this is not a job for the faint hearted. Especially when the girls get thrown into shearing lessons themselves at the end of every two hour session. Most of the sheep have been dagged or crutched in previous weeks, which makes the main shear straightforward, but when you hear that most flocks are shearing twice a year, (we generally only do it once in the UK), you realise that these guys really do work hard for their money.

The Loo with a view. (otherwise known as the Dunny)

One of the best gadgets we’ve bought in a while, those marvellous people at Milwaukee keep coming up with things we never knew we needed. Here is a staple gun, the best part of it being that it doesn’t need a gas bottle, like most other makes do. It can generate the power to shoot the staple into the post just with battery power, and it is surprisingly light too, so makes stapling up the simplest and most enjoyable part of fencing.

Outgoing NFU President Minette Batters came to tea with Dorset NFU at the Langton Arms, the last stop on her Farewell Tour of the country. About 15 farmers attended to present her with a beautiful platter created by Jo Burnell , potter, of Winterbourne Whitechurch. We had a fascinating and wide ranging conversation about many of the current issues facing UK farmers, with the benefit of Minette’s wisdom and experience. She has been in the leadership team of the NFU for 10 years and has as President for 6 years seen us through some of the most potentially traumatic events UK farming has faced since the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846, including leaving the EU, the Ukraine War, and Covid pandemic. She has worked tirelessly, on farmers behalf, with an endless stream of Prime Ministers and Defra secretaries of state, each of whom has had to be carefully introduced to the intricacies of UK farming. In spite of the NFU’s best efforts, some of them managed to do irreparable damage, specifically Boris Johnson and his oven ready deals with Australia and New Zealand, where he gave away so much for so little, which any negotiator with any brains would not have done.

This year’s NFU National Conference took place in Birmingham, where Rishi Sunak was the headline political guest on day one. He addressed conference and was then interviewed on stage by Minette who demonstrated what an accomplished politician and adversary she has become. The PM tried very hard to convince the audience that ‘He has our backs’, and in terms of the new schemes of public money for public goods that his government has introduced, they have admittedly done quite a good job, the scheme works, is easy to apply for, and is already paying out. However, it is still the case that farmers’ main responsibility is growing food to feed the nation, but with the disappearance of the Basic Farm Payment, food gets no support now, and yet the government doesn’t seem to be the least concerned about the long term effects of this.

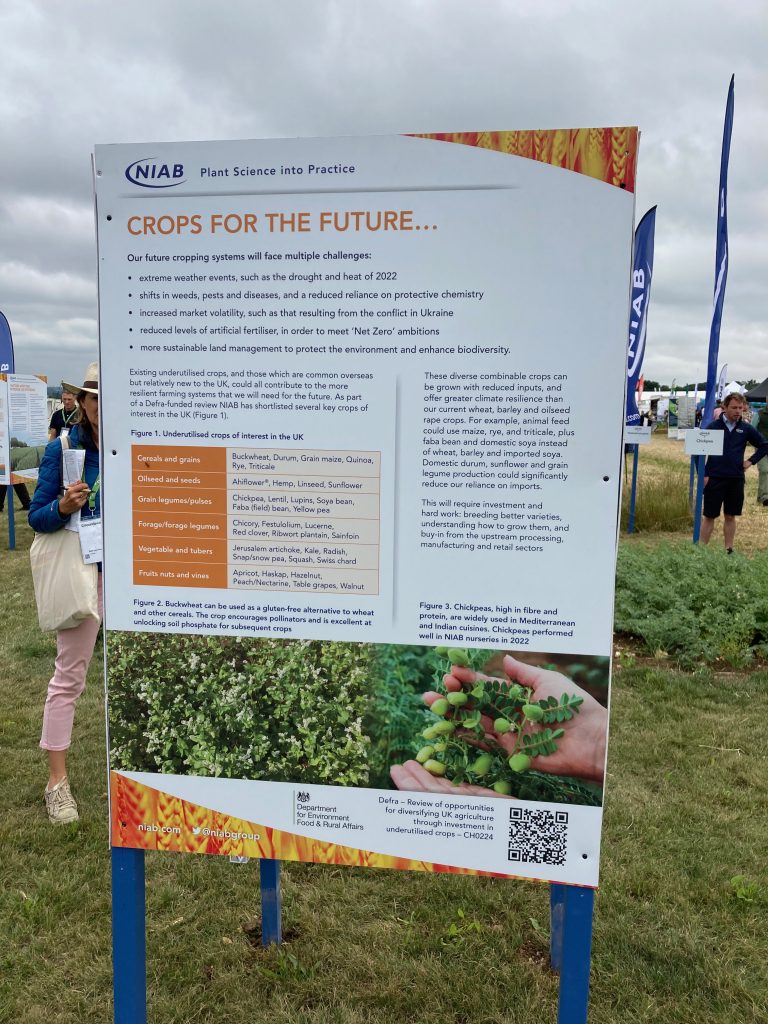

A great deal of food is already imported into the UK which is grown abroad in ways which are illegal for UK farmers to use. Ruthless retailers and other operators in the food industry care not a jot, and conspire to keep the consumer in blissful ignorance. We have had so many restrictions imposed over the years on how we grow food, in particular in the pig and poultry sectors, also oilseed rape and milling wheat, and yet we are still expected to compete with the imported stuff grown with illegal chemicals or welfare standards. How long do we expect this to go on before very many farmers give up growing food entirely and simply take the money on offer to grow flowers, bird food and trees? It seems to make more sense to me to do all of these things, including the growing of food, and learn how to produce food in a more sustainable fashion, reducing our impact (pollution and loss of habitat), whilst producing healthier food with fewer potentially harmful inputs.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m001wr47This is a link to an episode of On Your Farm on BBC Sounds, with Minette, recorded shortly after her term of office concluded after conference. It is a lovely walk around her farm on a sunny day recorded last week, with reflections on her 10 years at the top of her game with the NFU, and her plans for the future.

https://podcasts.apple.com/gb/podcast/leading/id1665265193?i=1000631081733Another interesting extended interview featuring Minette, can be found on the Rest is Politics -Leading podcast with Rory Stewart and Alistair Campbell.

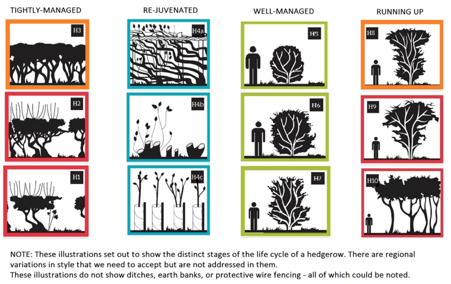

Brendan has been working hard on hedge laying this winter, when the weather and cattle work has permitted. He has become very adept at laying down the old and brittle stems of the shrubs in the hedge without them snapping, as can be seen in the picture. It will be lovely to see how this leggy old hedge will look after it has put on a few months growth later in the year.

Another hedge has also been given loving care and attention, at Folly, where a very over grown, predominantly hazel, hedge has been laid, staked, and bulked out with ‘dead hedge’, cut lengths which will provide protection from marauding wildlife, and at the same time protecting the new shoots that will soon be emerging. Fred and Rosie are preparing a flower garden, demarcating the site and opening it up to sunlight have now led to the purchase and planning of a polytunnel, and the planting of the first plants.

Not something we’ve found in a round bale of hay before, but an eagle eyed operative spotted the remains of a snake in the bottom of the cow’s feeder. Hard to identify, as we hardly ever get to see snakes, but we assumed it must be an adder.

It had to be 9.00 on a Monday morning on the main road at Durweston lights, someone had left a gate open, and the traffic was backed to the village before we caught up with them. Luckily a couple of kind farmer types had managed to block the road and turn them back, and being tame, and partial to toast, which I was carrying, they were soon led to safer pastures. They must have realised we were planning to move them that day, and decided to save us the trouble of getting the stock trailer out.

Next month